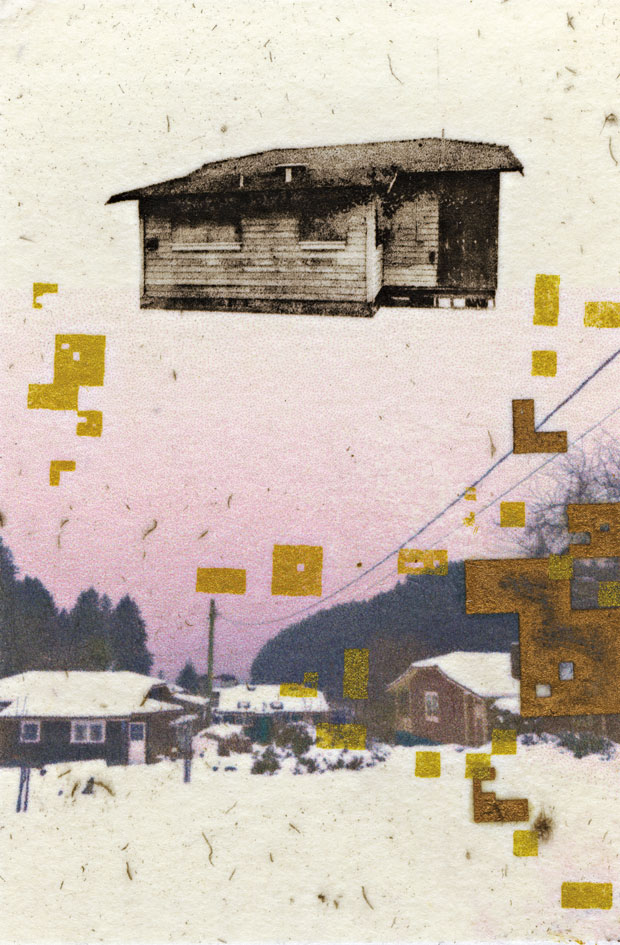

Twelve Points in a Classical Balance by Chung Hung. Photo by Stephen Henighan.

Of all the legacies of the West’s Cold War struggle against Communism, the most destructive is anti-Communism. This vacant doctrine, proposing no positive model of society, condemned any deviation from orthodoxy as the advance guard of Soviet subversion. In the United States, where it was refined, anti-Communism enjoyed two high points: the late 1940s and early 1950s, when it fuelled campaigns to expel everyone from civil servants to Hollywood scriptwriters, from their jobs; and the 1980s, when President Ronald Reagan employed the rhetoric of anti-Communism to fund murderous proxy wars in poor countries. Anti-Communism gripped the West and its allies. From 1937 to 1957 the premier of the authoritarian government of Quebec, Maurice Duplessis, used the Padlock Law to expropriate houses or businesses that were “propagating Communism.” In apartheid-era South Africa, the Suppression of Communism Act silenced government critics and banned dozens of books. In many Latin American countries, particularly during the Reaganite 1980s, students, teachers, journalists or union organizers who expressed ideas seen as “Communist” were jailed, tortured or disappeared. In many cases, anti-Communism mutated into an all-purpose ideology of hatred that targeted people for being men with long hair or women with short hair, or foreign or Jewish. The paranoid legacy of anti-Communism lives on in contemporary nativism, racism and Islamophobia, yet at a formal level this ideology has been retired by Western governments—except in Canada.In 2007, Secretary of State for Multiculturalism and Canadian Identity Jason Kenney, the standard-bearer of social conservatism in Stephen Harper’s Conservative government, visited a statue of a man crucified on a hammer and sickle that had been erected in a private park in Scarborough, Ontario, by Canadians of Czech and Slovak descent. The same year, in Washington, DC, President George W. Bush inaugurated the Victims of Communism memorial, a replica of a statue created by Chinese students during the 1989 Tiananmen Square uprising. Kenney persuaded Prime Minister Harper to plan a memorial in Ottawa with the same name as the one in Washington. But whereas the American Victims of Communism is a discreet three-metre-high statue, the Ottawa project was envisioned as a series of tiered concrete rows, rising to a height of fourteen metres, that would face a gargantuan concrete bridge across an empty concrete square. The memorial was to loom over the Supreme Court of Canada in exhortation to those who interpret the nation’s laws to implement the ideology of anti-Communism. The irony that, in its hulking gigantism and strident lines, the proposed memorial resembled a Communist relic, such as one might find in Russia or Bulgaria, rather than a freewheeling expression of liberty, was lost on the project’s official promoters, a nine-person board who call themselves “Tribute to Liberty.” Seven board members identify themselves in their biographies as being of Eastern European heritage; two identify as being of East Asian heritage. Most have ties to the Conservative Party.

Under Minister of National Heritage Mélanie Joly, the Liberal government of Justin Trudeau is perpetuating this avatar of anti-Communism. Adding the words “Canada, a Land of Refuge” to the “Victims of Communism” moniker, Joly has asked five companies to compete in the creation of a new design. The Liberals plan to move the memorial’s site to the Garden of the Provinces and Territories, diagonally across the street from the national archives. Containing the floral emblems of the provinces and territories, the garden assembles essential symbols of Canadian unity. The modernist statue Twelve Points in a Classical Balance, a celebration of Canada’s ten provinces and (prior to 1999) two territories, by Chinese-born Canadian artist Chung Hung, will undergo “sensitive and appropriate” removal to make way for the inclusion, as one of the constituent elements of our nation, of a shrine to anti-Communism.The declared intention of the memorial is to honour people killed by Communist regimes, as the planned National Holocaust Monument will commemorate victims of the Nazi genocide. But the two are not the same. The Holocaust memorial will have its own site; Victims of Communism, by contrast, will weave the creed of anti-Communism into the national fabric. Minister Joly’s addition of the words “Canada, a Land of Refuge” accentuates this bias by suggesting that Communism was the only Cold War ideology that produced refugees.

This erases the traumatic experiences of those who fled oppressive Cold War-era anti-Communist regimes in Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, Chile, Brazil, Colombia, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Spain, Portugal, Greece, the Philippines, Iran, Indonesia, East Timor, Egypt, Democratic Republic of Congo and South Africa, among others.

The memorial’s addition to the Garden of the Provinces and Territories constitutes a message from the Government of Canada that if your uncle died in the Gulag we respect your suffering, but if he was tortured to death by the Argentine junta you are a non-entity, if not an enemy of the state. The victims of anti-Communism should receive the same respect as the victims of Communism but they are unlikely to get it. Belonging to communities almost none of whose members have been as financially successful as the most affluent Eastern Europeans and East Asians, they are at a crushing financial and organizational disadvantage. When I asked leaders of affected communities to go on record, people I’ve known for years declined to respond. According to one leader, who asked for anonymity, many of the victims of anti-Communism, being less integrated into Canadian society than the victims of Communism, have little emotional engagement with Canada’s choices of symbols. More involved in the politics of their families’ countries of origin, they are conscious of being less fluent in English, less white and less aligned with Canada's power structures than their opponents. They perceive their host country as democratic, yet, as the planned memorial confirms, supportive of the anti-Communist ideology that persecuted them. The night in 1973 when a Chilean friend of the community leader I spoke to arrived in Canada as a refugee, the hotel where he was lodged was picketed by Croatian-Canadian demonstrators demanding that he be expelled from Canada and sent back to General Augusto Pinochet’s jails as a “Communist.” He’s never forgotten his Canadian welcome. As oppressive as he finds the Victims of Communism memorial, he’s afraid of speaking out against it.