Woe is me! to the land of what mortals am I now come?

Are they cruel, and wild, and unjust?

or do they love strangers and fear the gods in their thoughts?

––Odyssey, Book VI, 119ff.

~ ARRIVAL ~

Donousa is not easy to leave and for the past three weeks we haven’t had sex with anyone but each other. The spotty mobile reception is frustrating. Our app tells us the nearest adventure is 21 kilometres away, the next island. We’ve resorted to old-fashioned cruising methods: time wasted, looking ridiculous. We focus on each other and tire of eating souvlaki every day.

It’s seven thirty in the evening and I sit with Sebastian, chess pieces between us, at To Kyma, the port café. From this perch above the harbour and boulder jetty, half the island awaits the arrival of the Express Skopelitis. The 380-seat ship is the island’s lifeline, in service three times a week since 1956.

Sebastian calls the boat the “Scrofulous,” but it causes other ailments. It sets sail even in the choppiest of weather, vomit painting serifs on its blue lettering: Small Cyclades Lines. When they stagger off-board, some passengers should be met by an ambulance.

They land on Donousa, the remotest Cycladic island, chipped from the island group, surrounded by rough sea. A speck of dirt on my map turned out to be a single mountain peak with blunted edges and bleached cube houses. It is where the Romans sent exiles, thinking the island had no water. Summer bakes its hillsides of desiccated thyme, sempervivum and sage. Only the underwater chasms give Donousa colour: transparent depths, picked clean of seaweed, bare as a fish skeleton.

Sebastian taps his finger and I consult Logical Chess: Move by Move. Today, we learn from a 1928 game in Evian, the chess gods making our choices. The Skopelitis, meanwhile, is a fleck suspended before the mountains of Naxos and the sunset. Each time we move a piece or force down some eggplant bloated with oil, the boat grows larger. Its white hull approaches, pounding the surf and rocking side to side simultaneously, like something cruel children might do to an animal in a box.

The sea grows dark; we order another quarter litre of wine. The ship’s horn and motor amplify, as does the chatter of old women in black on the quay. Men groan in on motorbikes and skid within inches of them. The boat rounds the harbour and its rear rises to the dock. Sebastian and I forget the game, entranced as the seasick unload.

We examine each face, looking for someone sexy. The friendly (but too familiar) brothers who work the beach café stride on board against the lurching foot passengers, to collect bags of potatoes, peppers, fava beans. The priest (married, straight) directs acolytes (ditto) to portage cucumbers, wine casks and an animal carcass for the saint’s festival, or panegyri, tomorrow night. The musicians (all over sixty) are photographed by two German matrons with walking sticks. A luxurious beard parts the crowd and Sebastian knocks over a bishop. But the man is kissed by the henna-haired creature from the bakery. Barrels and barrels of feta follow. We aren’t that excited about the feta.

We stumble home to our domatio. Past the bakery and the ATM, along the town beach, the sand is deep, and we get our runners wet. There are no lights down here past midnight. Reeds click in the wind, a shape moves in the surf. As we reach the point farthest from the port lights, where the waves feel suspended, we hear a splash.

A man materializes. We shrink back. He seems to have come directly from the Aegean. It is too dark to decipher much except his blond sailor hair, translucent in the rising moon. He should be covered with seaweed. He should not have dry clothes. We hesitate at the familiar tension as we stand before him. I am about to nod in the direction of the reeds, but we hear his voice, focused in his nose, a French accent.

“Where is the beach at Kedros?” he asks.

We point down the coast: a path over the ridge, down the cliffs, a journey you shouldn’t make at night.

Just as quickly, he disappears.

Sebastian shakes his head. “Fuck this island.”

“Where did he come from? He wasn’t on the boat.”

That night, I find it hard to sleep in our domatio, like ones we have stayed in all over Greece with its tiled floor, shuttered windows, laundry line and blue door. Sebastian and I are cramped under the white linen of a single wooden bed. He eventually pushes me into the next bed––three are lined up in the room––but even on my own, I feel confined and tear off the sheet.

In just my boxers, I stand and walk barefoot to our terrace and stare over our moonlit row of basil plants. The port of Stavros has more electric lights than the rest of the island put together. Its streets of arched, whitewashed houses resemble a skeleton. The town beach is darkened. There is no one, not a sound, not even footprints that might come directly from the sea. There’s just meltemi––the wind.

~ NIKOZ ~

In the morning, we don’t need to discuss where we are going. We pack up our beach towels and take the coastal path. The ancients chopped down the trees for their ships; to one side are stone terraces retaining topsoil, where goats nibble at the nettles, and to the other is the ribbed sea. It’s a hot walk up the hill. At night, it would have been cool. It would have been all stars, as if you could step into them.

We reach the cliff top, its precipitous trail. The beach below, smeared as if by a great thumb, is fringed by the eponymous cedar trees. Kedros. Between them, we can just make out the occasional tent tarp, hanging laundry, and nudists of the campsite striding into the Aegean. Far out in the bay is the carcass of a sunken World War ii German longboat.

I can’t spy the shock of blond hair. It’s only as the trail kicks out, at the bottom, that a cedar tree, sheltered by the hillside, comes into view. The stranger sits under its umbrella.

Sebastian and I turn to each other wordlessly on the path. The man must be in his late twenties, just a few years younger than me. His sun-brushed body is shaded under the branches. He wears a rough linen shirt, his chest tightening under the open V. I wonder if he has satyr legs, whether little horns are hidden in his sun-bleached locks. But as we grow close, he pulls his bare legs from his sleeping bag.

The stranger looks up, smiling, and starts talking right away. At first, I am only half-listening. He has pale skin. His nose is red, peeling; it seems he decided long ago to forgo sunblock.

“It smells so beautiful sleeping here,” he tells us. “I’m shielded from the wind and the sun.” He rummages in his overstuffed backpack, from which I see the top of a laptop and the bell of a clarinet. Eventually, he finds a bottle of milky liquid in the folds of his sleeping bag. It looks like he spent the night with it.

“Here, you must try this,” he offers, not getting up.

“Try what?” Sebastian asks with a faint smile.

He blinks. “It’s goat milk. It’s still warm.”

The stranger goes on to explain how you need to move fast, grab the goats by the legs, then milk them. A local shepherd told him it’s better for the digestion mixed with water, but he likes it pure.

Sebastian takes a sip and stares down the barrel at the young man’s body.

He offers me the beat-up bottle and I try.

“Delicious, isn’t it? You can taste the island.” He laughs. “Hell, you can taste the ass of the goat.”

“I’m glad you didn’t get lost last night,” I tell him.

He blinks and cocks his head.

I assumed he had already recognized us.

The stranger stands and introduces himself as Nikoz, short for Nikolaz. His mother wanted a name that was both Breton and Greek. Nikoz can also be read as Nikos. Nicolaus sylvestris: the one who walks the ridge at night, with only a small backpack, who falls asleep under a tree, who wakes to the sound of the surf.

I introduce myself but Sebastian doesn’t offer his name. He shakes the stranger’s hand instead.

Sebastian and I sit at a low table in the beach café. The family makes fennel pie and salads with ingredients from their irrigated field behind Kedros. On the lunch menu, we see rizogalo, or rice pudding. Michaelis tells us it’s from the goat they milked that morning.

In the shade of the café, with a view to the band of blue, I see Nikoz swimming distantly and I argue with Sebastian. We should change how we travel. Why do we have a heavy rolling suitcase? Why don’t we sleep on the beach? There will be campfires and drinking and then who knows what happens. Sebastian reminds me of the virtues of a room with a shower and toilet.

“You wouldn’t last a half hour,” he tells me. “You’d get cold or bitten, or be allergic to something.”

We look up from our table and Nikoz is standing before us. I thought I’d just seen him out in the bay and don’t understand how he got to the café so quickly. He pulls up a wicker chair, his feet covered with sand, his clothes dry. In one hand is his smartphone, in the other The Master and Margarita.

Michaelis takes our order. “You don’t even want a glass of water?” he asks Nikoz, who shakes his head.

Nikoz tells us many things in the café. How he lives in the Greek islands in the summers and has learned the language. He spends winters in the “South of Arabia,” which means Oman, leading trekking tours for French adventure companies. He lives out of a backpack; it’s been years since he’s been back home.

“My favourite island is Amorgos.” He points across the water. He talks about the depth of the sea there, the shafts of copper mines filled with saltwater. “You come out of the blue, amazed it hasn’t dyed you. My friends are there; there’s a great community in the Chora.” Arabia also has miles of coastline. Hospitable people, who would give you everything. Nikoz loves these stark landscapes: sea, desert, and––when he was in Russia, travelling by train through Siberia––steppe and forest. “Russia has this soul, you can’t imagine. I met shamans in the Urals. Once I walked into the mountains, followed by a pack of wolves through the ravines. There was tension between us, yes, but also communication.”

I ask if he has been as far as Kamchatka, and he says he has. And to Baikal, where you look across the lake as if it’s the sea. “Unimaginably deep.” He visited all these places from St. Petersburg, where he studied opera singing. “Yes, I met great artists in Russia. They are the most intelligent people, the deepest, but also the hardest to know. But once you do, they are the most loyal of friends.”

I notice Sebastian has picked up his book from the table. He reads until Michaelis returns with our food––the fennel marathopita specked with sesame, a Greek salad with a block of feta drizzled with oregano and olive oil, and the pureed fava, homemade bread––and I nudge Nikoz. “Are you sure you don’t want anything?” He hesitates before ordering a dakos. Michaelis brings a Cretan rusk with fresh tomato and feta.

Nikoz then asks us if he might come to our room later. He has nowhere to charge his computer. I tell him where we are staying and say that he should knock and see if we are in before dinner.

“A real room, a real bed!” he laughs.

“You don’t have an apartment somewhere––not in Amorgos?”

“No. Just my tree! Or I stay with friends.”

“You must miss living somewhere.”

“I do wonder what’s happened to my books.”

“Isn’t there some place you want to remain?”

“Not yet.” He wipes tomato from his face.

“I haven’t found it either,” I reply. “I used to look for the best place: making charts, comparing costs, amenities, climate––”

“You do that? I do too!”

“Well, all I can tell you is that place is not London or New York or those big cities.”

“I could never live there. The darkness, the rain, the stress. I can’t bear being underground on those trains…”

“It seems crazy to live that way.”

“You should try Amorgos!”

I think about this for a moment: a year on a Greek island, turning into two, or three, or a lifetime. “I could teach English––”

“You could! But first, a swim.” He smiles back at us, pulling off his shirt, skipping toward the blue.

Sebastian and I sit, reading, wondering what to do with Nikoz’s phone, which he left on our table. An hour passes, perhaps longer, and finally we just give it to Michaelis and settle the bill for lunch. Nikoz’s dakos is on our cheque. Sebastian says, “Well, he’s probably still at the beach, planning to come back.”

“Michaelis could separate the bills.”

“I don’t mind buying him a dakos,” says Sebastian.

As we count out our money, a French woman at the bar, whom we’d met a few weeks earlier––invariably in black, even her bikini––turns to us between drags on her cigarette. “So, you’ve met the Breton sailor,” she says, calling him le mythomane. She’s also sleeping at the beach. “He was up all night telling… stories.” She exhales and stubs out her cigarette glumly, before putting on her shades.

Sleepy from lunch, we trudge down the beach, on our way back to town, squinting as the naked people come in and out of the water, and chuckle about all the places they must find sand. I have carefully removed as much I can, even from between my toes, before putting on my shoes. I look up and down but do not see Nikoz. Ah, there he is! Under his solitary tree, eyes closed, sitting in the shade as the sun crackles, playing the clarinet to himself. I count the number of steps up the cliff until the music can no longer be heard.

~ PANEGYRI ~

Sebastian wakes from our afternoon nap to buy bottled water and instant coffee from the expensive grocery market. I take a long shower. The soap smells like the beach, of kedros. Why does bathing bring out sunburn? The bathroom window overlooks the hillside, the bleating of goats. Late sunlight pours in. In minutes, the tiled floor will dry. I’ll fall back into the white sheets, read until Sebastian returns. Rest up a little more. Tonight is the festival, the panegyri.

Then I hear something. Sebastian wouldn’t knock. I rinse and grab a towel. The shutters are open, latched against the wind; I see the shock of blond hair. Nikos leans through the window and gives a little grin.

“Hey! You found us. Just a minute,” I say, as he takes in the room. I can’t tell what is inside and what is outside. I miss the removal of an intercom or telephone, the chance to put myself together. But I also want to feel his eyes on me as I look around for underwear, except Nikoz waits patiently with his back to me, looking out over the basil plants, down to Stavros, where there is already music.

When I open the door, I see him from the waist down, his laptop in a battered plastic bag.

“You have an extra bed!” He looks at the three in a row.

My lips tighten. His feet are all sandy. He isn’t wearing any shoes. He touches the end of the bed, to test its firmness, and looks back and smiles. “And a shower!” he adds.

He gets down on his knees by the bed and puts his computer on it, plugging it into the wall. “That should do it. Do you mind if I take a shower?”

I blink. “No, of course not.”

“Amazing!” He takes off everything in front of me and steps into the bathroom. What feels like a long time passes. I clean up the sand, sit for a while at the end of my bed, then go outside and watch the sunset, before the door opens and Nikoz’s hair is all standing on end, like a bushel of wheat, and he is rubbing his shoulders with Sebastian’s towel. Spaced all along one side of his chest are angry welts.

“That was amazing. How much are the rooms here?”

I tell him, and he muses that he really should get one. Perhaps noticing my gaze, he points. “You see, I got bitten under that tree. And when the wind was up, it was hard to sleep.” He glances at the extra bed, with his computer on it, and says, “I better find a different tree.”

“I can introduce you to Maria downstairs; she owns the place. You can ask her about a room.”

But Nikoz shakes his head, not looking directly at me. “No, no, don’t do that. I want to ask around, find the best place.” He looks up after he has thrown on his sandy clothes. “What should I do about getting my computer back?”

“How long will it take to charge?”

“It’s slow. And when it’s done, the panegyri will be in full swing. But if you want, just leave the key under one of those basil plants. I’ll get it on my way back tonight. That is, if you’re still out dancing,” he suggests.

“Why––why don’t I just bring the computer to the beach in the morning. You see––” I pause. “Sebastian has the key. I don’t know when he’ll be back.”

I glance around the room, at the tables and ledges, to see if the key is somewhere obvious. Nikoz just beams his usual smile and says, “Of course, if that’s not too much trouble.”

It’s already dark as we walk into town, and Nikoz tells me there will be rebetiko at the port. Is it by chance that we are on the island for the panegyri? He’d come especially from Amorgos for it. There was already a score of activities I had missed, that afternoon and early evening: a Greek dancing lesson, a telescope that attracted every child in the village, then the procession and liturgy with the patriarch. I am only in time for the feast and dancing.

We continue across the town’s beach, where we had first met Nikoz, toward the lights and music. He stops halfway at the darkest point and brings one arm around my shoulder.

It feels somehow uncomfortable there, but I also like it. He turns toward the sea, bringing my attention to its silvery movement, the threads tying and untying. Then he pulls off his shirt and his pants again, and cries, “Come on!” as I hesitate. When he is halfway into the darkened water, I pull off my clothes and follow, reassured that below the surface he can’t see me naked. Once I slip into the waves, I feel the remarkable change, the way the Aegean removes every diffuse worry in its magnitude. Underwater, I even allow myself to open my eyes and look into the maw of the dark sea, and for once it does not terrify me. When I break to the surface, Nikoz is already back on shore, hooting gleefully, surprised when I tell him it was my first swim of the day. He points the way to the music.

As we come up the other side into Stavros, laughing, arms around each other, he tells me to wait, and walks over to the island’s lone bank machine.

He returns with his salty eyebrows furrowed.

“What is it?” I ask.

“It’s nothing.” He shrugs. “It’s just my card didn’t work. Not last night either. I don’t know what’s going on. Could you try? Maybe I could borrow fifty euros until my mother gets here in a couple of days? I can pay back everything then.”

I pause, then reach into my pocket. I’d left my wallet unattended on the beach as we swam and now it’s full of sand. I walk up to the machine and put in my card. It seems to be working just fine; it’s even asking for my code. But I can’t withdraw money: I have typed in the wrong code, just once. I wait, withdraw my card, then turn to Nikoz and lie to him for the second time that evening.

It’s probably the panegyri. The machine is out because there are so many people on the island. Or the circuits are down. It’s such a tiny island. Did you check with your bank? Maybe your card doesn’t work in this machine.” I am talking too much. I’m grateful when we run into Sebastian below To Kyma, two big bottles of water hanging from a plastic bag.

“Come on,” says Nikoz, a little glumly.

“What is it?” Sebastian asks in my ear as Nikoz walks a few steps ahead.

“I’ll explain later,” I tell him.

In a line, the musicians hold their instruments. The table edges are painted blue, with white paper cloths that flutter. The Donousans have made food for the entire island: Greek salad, goat stew served with roast potatoes, free-flowing glasses of ouzo and rosé. I wonder, isn’t this a Greece in crisis? How can they afford to feed everyone, even the tourists who can afford to pay for it? Sebastian says something about the hospitality of the ancients and how you never know if a guest might be a god.

“You can’t flirt with the god?” I ask.

“Flirt, just don’t touch.”

“What if he’s hot?”

“So hot he’ll burn you to a cinder.”

“Hot and dangerous then!”

Sebastian says I wouldn’t stand a chance. I wouldn’t be good at being humble, going unnoticed, making my offerings. “Just never give him your name,” he warns. “Or he’ll come after you.”

“I don’t mind coming first,” I riposte, and Sebastian gives me a slap.

The music starts slow. We shuffle in circles; it’s not hard to catch on. A young woman takes Nikoz’s hand, and I find mine in his, joined soon by an old woman, children, and the German matrons. Voices join in, and then a solitary old man begins to sing. I thought sirtaki was about imitating being drunk, but when we break from the crowd and find ourselves at the same table, Nikoz tells me the meaning of the Cretan dance is deeper. It is like walking on a––he looks for the right word in English, unhappy with my suggestion of tightrope. It is like stumbling through life down a slackline. He gets up from the table and sways into the crowd.

There are more tastes––anise, raki, resin, rakomelo. Spirits cut with honey for the honey-eaters, for people who see a god in a man washed up on shore. The children dance in their circle, charming and clumsy. A young woman enters the light, each of her movements more careful than the next. Nikoz approaches, puts one arm around her, says something in her ear. What did he tell her? What new lie? Something good! I look on, flushed with envy, as they disappear together for the rest of the night.

After a while, we get bored by the dancing that seems repetitive, and the circles of locals weary of including us foreigners. One man releases my hand when I stare too long and sends me spinning into the crowd. Better to walk down to the darkened beach again, follow it to our room, and fall into one of those drunken sleeps where you feel as dry as the landscape.

~ ARRIVAL II ~

It is late morning when I carry Nikoz’s computer down the cliff path. He is not under his cedar tree, but his sleeping bag is neatly folded over his backpack. Michaelis takes the laptop behind the bar of the café, and I walk straight back to Stavros and fall into bed, where Sebastian is still sleeping. We wake mid-afternoon; I smell sweat and aniseed on us and blink in the severe sunlight as I walk out onto the terrace.

Days pass. We see Nikoz sometimes down by the beach, but I notice his backpack is no longer under the cedar. Maybe the woman at the panegyri took him in. Maybe he repaid her in bedbugs. Sebastian and I enjoy making fun of le mythomane. The traveller with a holy mother. Of virgin birth. In communication with wolves and Russian shamans on the beach at Baikal. We compare him to characters in novels. Maybe he can’t return home because he’s wanted for a crime. We were street-smart about Nikoz.

It’s Sebastian’s move, as we peer down at the dock from our seats. The wind keeps blowing our pawns away. The crowd grows. Engines sputter. Boxes are unloaded. People hold on to their hats. The Skopelitis is late from Naxos and there is a hush around the dock. The musicians pull their instruments to their chests. A woman draws her child in.

We drink more wine. And then the boat finally comes into view.

Sebastian shakes his head at how the Skopelitis rises and falls. Then, as the boat hugs the jetty, it cantilevers entirely to one side. I imagine the disarray––the tables and chairs bolted to the floor unfastening––before the boat springs upright, around the breakwater, and into the harbour, where ropes are thrown to land, to steady its white body.

The silence evaporates as passengers emerge, falling into the arms of their relatives on shore. Those meant to continue onward to Amorgos debate vigorously about whether to reboard.

Leaning farther over the balcony, Sebastian points. Directly below us, obscured until now, is a young man in a pressed white shirt and linen pants. His hair is combed back and parted. He takes two steps forward, for off the boat comes a conspicuous woman who must be in her sixties, curated to look much younger, with a great mane of hair. A she-lion, remarkably unruffled, in an Italian suit jacket and cropped palazzo pants, she pulls a leather valise. After they embrace, she shrugs toward the boat with a casual gesture and pulls out a cigarette from a silver case. Her tailored satchel goes snap. Then, in the absence of a porter, Nikoz takes over the luggage and gestures the way into town.

The next day, we get a knock on the door. He is well dressed, in leather shoes, and a straw hat you might see on an Impressionist painter, inviting us to come by his hotel at dix-huit heures for an apéro. Nikoz’s tone seems clipped. After a day at the beach, we find ourselves fishing in our bags for something more elegant than tank tops and beach shorts and can’t come up with anything except t-shirts and jeans.

We are surprised by the garden hidden behind the wall of reeds on the town beach. The houses are all brightly painted. A cat runs out of the manager’s apartment, leading us to the last villa behind a row of palms, where on a terrace fringed with oleander, Nikoz and his mother bring out wine glasses and set a cloth over a wrought-iron table. The goddess gives us a smile that is both accommodating and indicates we have arrived too early. Sebastian mutters under his breath about le quart d’heure de politesse.

We chat as Nikoz bustles in the kitchen. His mother doesn’t talk about herself; she only asks questions. Sebastian speaks to her about his research––Rabelais, Pantagruel––while I say little, my eyes drawn to her son. The salon is very clean, with hardwood––not tiled––floors. Two separate bedrooms adjoin it, perhaps with their own bathrooms. I think about going inside, to help, but don’t.

Finally, Nikoz emerges with a plate in one hand and a chilled white in the other.

“Dakos,” Sebastian notes.

Nikoz’s mother brought the wine, a Muscadet, from their terrains near Nantes. It is dry, light, lemony, somehow perfect for this landscape so far from France. She tells us––the way parents do through others, to jibe their children––how Nikoz was never interested in the family’s wine business and probably started travelling the world just to avoid it. All those years in Russia. And in Oman. What kind of son had she raised to prefer those places to the Loire? Then she laughs and puts one hand fondly through Nikoz’s hair as he lowers his head to sip the wine. She sighs. “At least I’ve seen a lot of places I wouldn’t otherwise have visited.”

Nikoz doesn’t say much for the rest of the apéro but he drinks three glasses.

Sebastian and I walk back in silence down the beach. Neither one of us feels hungry enough for dinner. We walk up to our room with its simple balcony and four basil plants. I look in at the three wooden beds and the rudimentary bathroom with its door half-open and turn back to look out at the sea.

“Doesn’t matter now. You’ll probably never see him again.”

“It’s just that… I feel like—” I hesitate.

“You want to stay somewhere better?”

“No. That’s not it. Not it at all. We lost, Sebastian.”

“Lost what? Him?”

“No—” I hesitate again. “No, not him.”

That night, Sebastian lies in bed reading and I take the book from his hands. We close the blue door, pull in the shutters, close the latches so the moon does not see us. The embroidered curtains breathe as we push the three single beds together, fill the cracks with sheets, and undress. We make love like old couples sometimes do, surprised to find each other.

~ AMORGOS ~

Sebastian is wrong. I do see Nikoz again.

A few years later, in late May, we find ourselves on the Skopelitis, after a winter in our light-deprived city. The arrival in the Mediterranean is a shock of wildflowers and salty air after being hunched at desks, hassled by sharp elbows on public transportation, and enduring other metropolitan stresses.

When the Skopelitis passes by Donousa, we stand at the railing. Our room’s terrace has someone else’s towel drying on it. To Kyma is full and spies our arrival. I recognize Michaelis next to a motorbike on the quay, but he does not see me wave. Soon enough, the jetty glides away as we travel on to Amorgos. I watch the other passengers on the top deck––young couples, old women in black, their husbands in flat caps playing with beads, children racing from one side of the ship to the other––and regret ever making light of this boat in a storm. We’re all on the Skopelitis, in some way or other. I even feel ready to help a total stranger if she needs to vomit down the hull. But the crossing is calm, and no one gets sick.

Amorgos nears. I am not prepared for what rises before me: the mountainous profile of a giant or a god, fallen asleep in his bath. Nikoz spends part of the year here. This I have not forgotten. But somehow, I push the information to the back of my brain as we go up to the old town, the Chora, and walk around the whitewashed streets.

In the morning, wandering alone through the warren and into a cavernous café, I find Nikoz sitting in his loose linen clothes, blond hair falling over his face, an espresso cup patient before him, and a dog asleep at his feet. I shouldn’t be surprised, but I am.

He looks up, in profile. I can see only one eye, but there is a moment of recognition: that first smile from Kedros––a warmth radiating from him, a breath of thyme, as if we are meeting on that beach for the first time.

And then––wiser––his expression hardens, and the light retreats from the windows.

“We’ve seen each other before,” he says.

“Yes,” I reply. “On Donousa.”

“But I don’t remember what you call yourself.”

“You’re Nikoz, right?”

He blinks, and we talk briefly about banalities––how long I am staying, how striking Amorgos is––but I have already broken into a sweat. I avoid his stare and make excuses, apologize for interrupting his breakfast, tell him to enjoy his coffee, and turn quickly to cross the threshold into the town’s meandering surfaces. The sun has vanished, several corners are between me and the café before I halt in a darkened lane––a wall at my back. My head darts––left, right, and up––to make sure I was not followed through the maze, before struggling to take a breath.

He hardly recognized me: a stroke of luck. I’ve gone unnoticed.

I am no one, and fold my arms against the cold.

The last thing I’d have given him was my name.

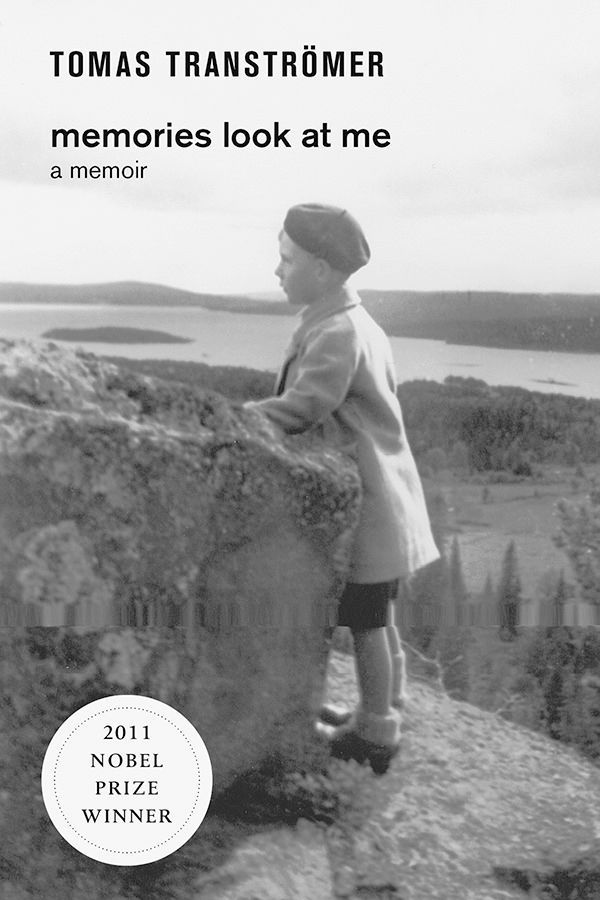

Image: Joshua Jensen-Nagle, The Awe in It All, 2022, giclée print face mounted to acrylic. Photograph taken in Milos, Greece. Courtesy the artist and the Bau-Xi Gallery.