Progressives are far less likely to be nationalists than ever before

For most of the twentieth century, and into the first decade of the twenty-first, a rarely remarked-upon anomaly distinguished Canada from other northern democracies: nationalists were on the left, not the right, of our political spectrum. In countries we regarded as being analogous to ours, nationalists were reactionaries: in France, the anti-immigrant National Front; in Germany, the doctrinaire Catholics of the Christian Social Union or small neo-Nazi groups; in Great Britain, insular Thatcherites and the xenophobic British National Party; in the United States, Reaganite Republicans who didn’t know much about the outside world and didn’t much care to, though they liked to bomb it now and then. By contrast, Canadian nationalists were lefties. They voted for the New Democratic Party or the Liberals. They supported nationalizing energy, kicking out American multinational corporations, fraternizing with Fidel Castro’s Cuba, stocking universities with Canadian, rather than foreign, academics and promoting bilingualism and multiculturalism.

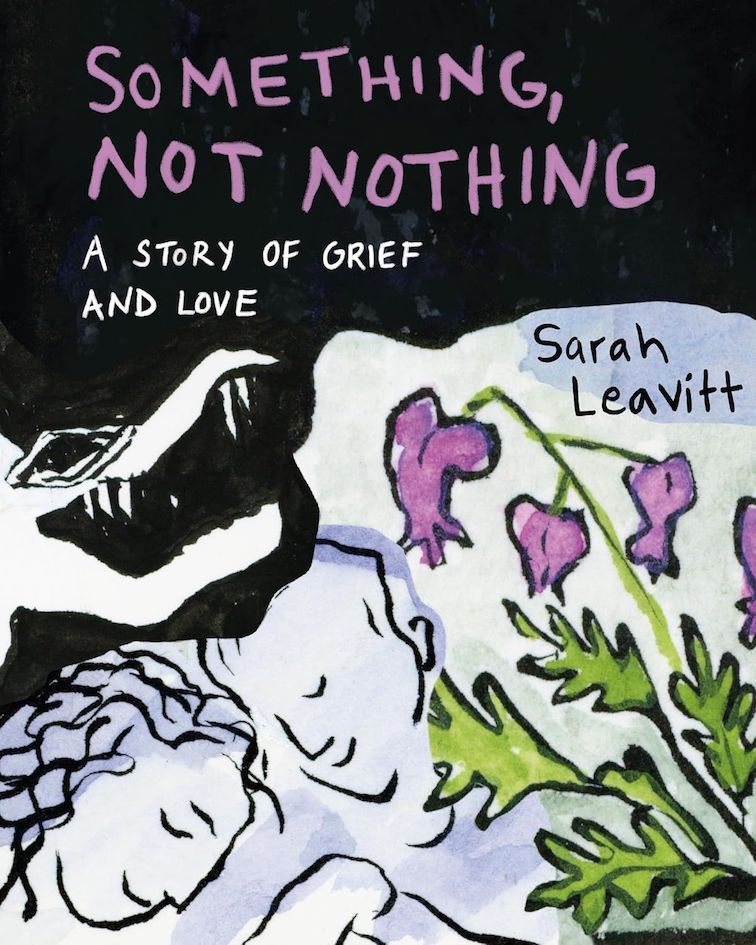

On the cultural front, Canadian nationalists asserted our particularity by supporting the CBC, campaigning for Canadian content quotas in television, film and popular music, and founding small publishing companies that aspired to forge a distinctive national literature. They rallied around books such as Survival: A Thematic Guide to Canadian Literature (1972) by Margaret Atwood, which was both a work of literary criticism and a left-nationalist manifesto, published by House of Anansi, a small publisher that Atwood’s friend Dennis Lee had helped to found. In the 198s and 199s, when free trade agreements enshrined the continentalism that nationalists battled against as government policy, Atwood and her supporters tried to “keep culture off the table” by protecting important national producers such as the “Canadian Publisher,” McClelland and Stewart. M&S brought readers the work of a whole generation of modern Canadian writers, as well as the New Canadian Library collection of rediscovered Canadian works from the past, which stocked CanLit courses in high schools, colleges and universities.

The other countries where nationalism was a left-wing creed were in what used to be called the Third World. The cultural histories of Mexico and Cuba brim with movements and policies that echo those of Canadian nationalism, from legislation to control US oil companies to national institutions to support publishing. Debates about national identity in Colombia, Peru or Argentina mirror certain Canadian preoccupations. In its rhetoric, Canadian left-nationalism hewed closer to the quest for a multicultural, post-colonial national culture in African, and some Asian, nations than to cultural debates in England, France or Germany.

The analogy between cultural dynamics in Canada and those in the Global South failed to fit when it came to the role of conservatives. In Latin America, the right was anti-nationalist, often barely masking its despisal of the national culture and cravenly worshipping the USA. Yet in Canada, until the 198s, conservatives had their own form of nationalism, based on nostalgia for British and colonial institutions; by today’s standards, many conservatives barely counted as being on the right. Lawrence Martin’s The Presidents and the Prime Ministers (1982) makes a strong case that John Diefenbaker, a Progressive Conservative, was the most nationalistic Canadian Prime Minister of the twentieth century. The philosophical bible of Canadian nationalism, Lament for a Nation (1965), was written by George Grant, a self-described “radical Tory.”

Over the last three decades, though, Canadian conservatives have abandoned Red Toryism and adopted a religious, gun-loving, sometimes homophobic or incipiently misogynist ideology closer to that of American Republicans. Progressives, meanwhile, have found that as globalization accelerates, the national boundaries they had depended on to build a forward-looking nation have become porous. At the same time, some of the blind spots of the nation as conceived by 197s nationalism have been thrown into relief. Among their other significances, the literary scandals of 216 and 217—the Steven Galloway case at UBC, the exposure of writer Joseph Boyden as white rather than Indigenous, the “appropriation prize” disaster—have discredited some of the key protagonists of Canadian left nationalism, notably Margaret Atwood, in the eyes of younger writers and artists. In the anthology Refuse: CanLit in Ruins (218), the first prominent book published about these events, Canada is not an aspiring social democracy but a cauldron of racism, colonialism and rape culture. Alicia Elliott, one of the volume’s most articulate voices, writes: “I’m not attached to Canada’s national identity, I have no stake in maintaining it, and I feel no pain dismantling it.”

This statement illustrates that being a progressive is far less likely to involve being a nationalist than used to be the case. Our nationalists, like those of other Western nations, are now on the reactionary right, fretting over racial diversity, “barbaric cultural practices” and asylum-seekers crossing the US border.

When Canadians cross the border, they find that in the USA Margaret Atwood is a feminist heroine, lionized by younger women at the 217 Emmy Awards for the television adaptation of her novel The Handmaid’s Tale (1984). In Canada, many younger women in the arts, who are aware of Atwood’s support for figures such as Galloway and Boyden, are wary of her and the allegiances she represents. In contemporary Canada a very different book of essays by a younger woman writer has captured the zeitgeist and sold far beyond its anticipated audience, as Atwood’s Survival did in 1972. Alicia Elliott’s A Mind Spread Out on the Ground (219) contains essays about growing up female, poor and Indigenous. One essay skewers Atwood’s contradictory views on Indigenous people. Yet one of the contradictions of globalization is that today Atwood, who in 1988 campaigned to keep Canadian culture off the free-trade table, and Elliott, who is a trenchant critic of capitalism, are both published by Penguin Random House, owned by the Bertelsmann Corporation of Germany. As Elaine Dewar details in The Handover: How Bigwigs and Bureaucrats Transferred Canada’s Best Publisher and the Best Part of Our Literary Heritage to a Foreign Multinational (217), McClelland and Stewart, “the Canadian Publishers,” is now merely a few desks in the Penguin Random House Canada office, where distinctions between the different imprints absorbed by this German-based company are no longer as significant as they once were. The Random House website’s publicity material for Elliott’s book downplays the fact that Elliott is Canadian, describing her work as being about “Native people in North America.” They avoid the Canadian term “Indigenous people,” which Elliott herself prefers, presumably for fear of confusing US readers, who are used to “Native.” Like the New Canadian Library, which Penguin Random House closed down when it absorbed McClelland and Stewart, the Canadian cultural context has vanished. Elliott, the young radical, stages her assault on Canadian nationalism from the point of view of an oppressed Indigenous minority, yet from the platform of a transnational corporation seeking to impose borderless markets. Indigenous peoples, whom left nationalists failed to include in their vision of the Canadian nation, and the continentalist—now globalist—corporations, whom left nationalists campaigned against, share an enmity toward nations with strong, centralized states. Left nationalism’s failure to develop a language to include Indigenous people and successfully challenge a globalizing capitalism that absorbs and neuters national cultural institutions has put an end to Canada’s distinctness as the rare northern country where nationalists were once on the left.