.svg)

Like other aspects of Canadian culture, our spelling, in spite of its second-hand appearance, is unique

Mordecai Richler, in a withering put-down, once dismissed the novelist Hugh Garner as “a good speller.” In the summer of 23, grinding through 16 Canadian books as a jury member for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction in English, I learned that for many contemporary Canadian writers, Garner’s level of dubious distinction remains out of reach.

It may sound perverse to become fixated on spelling while judging books for a literary prize. But serving as a juror for the Governor General’s Awards is like taking a gruelling road trip. You try to read a book every day and usually fail. On the days when you succeed, all the towns may not look identical, but there are, in most cases, distinct similarities: coming-of-age rites, failing relationships, cultural alienation. Like a child in the back seat longing to ask, “Are we there yet? Can I go back to reading for fun?” you count the passing fenceposts and giggle at the funny names on the mailboxes.

Standard Canadian spelling follows British spelling in many, though not all, cases. (The British drive on “tyres,” use “aluminium” siding and “realise” that they can be sent to “gaol.”) Like other aspects of Canadian culture, our spelling, in spite of its second-hand appearance, is unique. Part of our inheritance is a system for distinguishing between related nouns and verbs. The laminated card that authorizes you to get behind the wheel of a car is a “licence,” but the bar from which you take a cab home is “licensed.” Your son “practises” a sport, but you drive him to “practice.”

My students at the University of Guelph—and even some of my colleagues—are unable to master this system. Many of them write “colour” and “favour” and sometimes “centre,” as a basic declaration of identity, but after that they throw up their hands. Their confusions mirror the inconsistencies of the signs we see around us, where dissonant spellings mingle. Our newspapers offer little guidance. For years Canadian newspapers used U.S. spelling. In the early 199s the Globe and Mail, in theory, changed to Canadian spelling. Major Southam papers such as the Montreal Gazette switched to an impoverished version of Canadian spelling, adopting “centre” but not “colour”; under Conrad Black’s ownership of Southam, the “-our” forms came into use, though some American spellings (“traveler,” “two-story house”) were retained. Quill & Quire, another editing anomaly, brandishes a house style that juxtaposes the Canadian “offence” with the U.S. “defense.”

On the basis of my Governor General’s reading, I concluded that this half-eroded Canadian spelling is becoming the new norm. Older writers, whichever usage they preferred, were consistent. Margaret Atwood and Robertson Davies, edited in Toronto, used Canadian spelling. Mavis Gallant and Alice Munro, their stories edited at The New Yorker, conformed to American usage. Some younger Canadian writers with large U.S. audiences, such as Douglas Coupland and Naomi Klein, also employ straight American spelling. Coupland’s choice of spelling is consistent with his obsession with U.S. popular culture; with Klein, whose work defends local cultures, the spelling feels like a contradiction of the writing.

Most younger Canadian writers, even the best ones, spell inconsistently. Michael Redhill, in Fidelity, shuffles between “moulded” and “molded”; Ann-Marie MacDonald, in The Way the Crow Flies, alternates the U.S. “crenelated” with the Canadian “panelled.” While these writers’ lapses are rare, the inconsistencies run rampant in many who are less accomplished. Almost no Canadian writer—not even Leo McKay, Jr., who is a high school teacher in Truro, Nova Scotia, and one of the few Canadian authors who continues to write “snowplough” rather than “snowplow”—can resist the insidious spread of “license” as a noun. Any spelling adopted by high school teachers in Truro, Nova Scotia has become the Canadian standard.

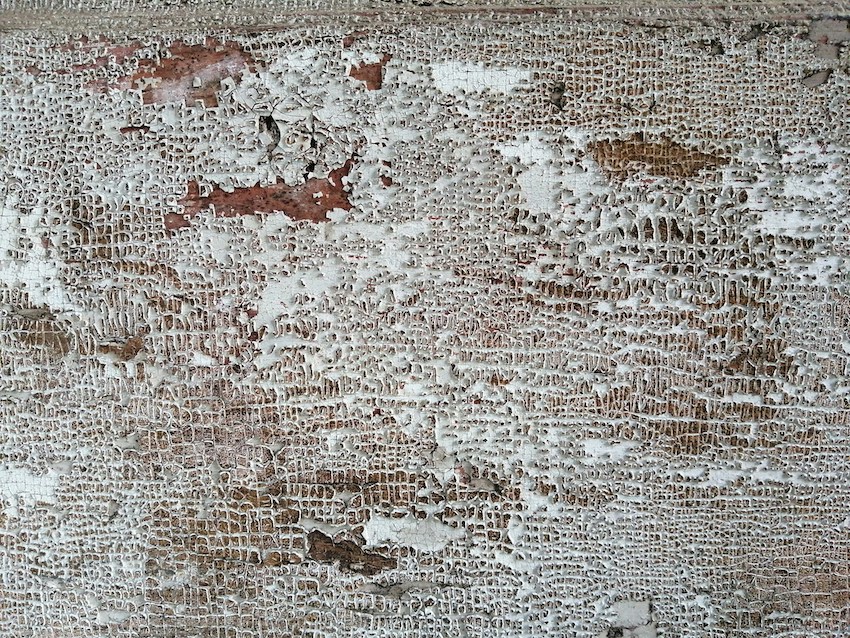

The case of “licence/license” and “practice/practise” shows how inconsistency (also exemplified by hyper-corrections such as a “licenced” bar or an “honourary” consul) is the hallmark of cultural erosion. In the Ottawa Valley village where I grew up, grade four girls from families with modest formal schooling would chant, “‘Ice’ is a noun so when ‘practice’ is a noun you write it with ‘ice.’” This dictum enabled them to disentangle “licence” from “license” and spell “defence” correctly. Such seemingly trivial ditties are the bricks and mortar of a culture.

It is tempting to shrug off the scattershot spelling of current authors, attributing it to an uphill struggle against U.S. spell-checking programs (although most computer programs now offer a Canadian spell-check option), or seeing in the inconsistencies a typical Canadian compromise between American and British customs. But this won’t wash, because current spelling is too irregular to fit a defined pattern, and most publishers no longer enforce a uniform house style. A conscious move away from British spelling toward American forms might be interpreted as an ideological statement in favour of integration into U.S. culture—and to some extent the promotion of U.S. spelling in Alberta and British Columbia may be seen in this way. (Hence the unusual spelling career of the B.C./Alberta novelist Gail Anderson-Dargatz. Her first novel used U.S. spelling; after acquiring a national audience she switched to Canadian spelling.)

To state the spelling question in terms of British versus American is to misunderstand it. Canadian writers long ago forged distinctive spelling conventions. The question is why—without any of the passion that swirls around spelling wars in countries like Germany or Romania—these conventions are fraying even as they have been consolidated by the publication of volumes such as the Oxford Canadian Dictionary (1998). My summer reading turned up a “theatre” here, an “odour” there, with other spellings intermittently Americanized; where the authors stumbled, the editors were incapable of picking up the slack. This is not a conscious decision, nor is it trivial: it is evidence in microcosm of a culture that is being forgotten.

.jpg)