The village itself stands as a remembrance of things past, peaceful (in spite of the traffic), uncluttered (in spite of the tourists), full of the particular light

Auvers-sur-Oise is a town of ghosts. Among the summer tourists and art-loving pilgrims who visit Auvers from all over the world, drift flocks of long-dead artists with folding easels and boxes of paints, who a century ago would disembark every week at the small railway station. Some are admiringly remembered: Cézanne, Corot, Pissarro. Others, such as the talented Charles-François Daubigny—in his day the most celebrated artist of all, are now little more than footnotes in the history of art and a bust in the town centre. Many more, who inscribed their names on their canvases with such ambition and care, have long been forgotten. Down the winding streets or on the riverbank, by the towering church or in the sober graveyard, visitors can sense their anxious ghosts in oil-smeared smocks and berets, trying to draw the visitors’ attention to a field, a tree, a house that in spite of two world wars and countless real-estate developers, once captured the painterly eye and still stands immutable. But the presence most strongly felt is that of an anguished, impoverished and visionary genius who came to Auvers in the summer of 1890 and died here nine weeks later from a self-inflicted gun wound: Vincent van Gogh.

Van Gogh arrived in Auvers looking for a place to work and to free himself from the nightmares of the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where he had chosen to intern himself a year earlier, suffering from hallucinatory fits. Theo, his beloved brother, had suggested Auvers, not only because it was a well-known artists’ colony but because (Pissarro had told him) here lodged the art-loving Dr. Gachet, amateur painter and homeopathic physician, who could look after him and follow his convalescence. Van Gogh found cheap lodgings at the Café de la Mairie (today Auberge Ravoux) where for three francs fifty a day he had a small room under the rafters and three meals a day. The only cure for the seizures, the doctor assured him, was to paint.

On Sunday, July 27, Van Gogh left the café after lunch carrying his paintbox and easel. He returned long after supper was over and went straight to his room. When the charitable patron, Monsieur Ravoux, went up to see him, he found the painter in bed, covered in blood. Van Gogh told him that he had shot himself so that “the misery won’t carry on forever.” Theo arrived the next day and for many long hours sat by his brother’s side. For a while he seemed to have recovered: he talked lucidly and smoked his pipe. Then, barely two days later, on July 29 at one-thirty in the morning, apparently without pain, he died.

Van Gogh’s room is today a dignified memorial to the artist. Hidden above the restaurant, up rickety wooden stairs, the room has nothing in it except the bare walls. Most visitors would expect to see the bed and chair rendered famous in his paintings, but these belong to other rooms, the one in Arles being the best remembered. Visitors are therefore forced to furnish the room in their imagination, to seek (as in the Auvers landscape) the correspondence between the tangible stone and the shapes and colours conjured up in Van Gogh’s work.

Set in the very heart of Auvers-sur-Oise, on the obligatory road from the train station, the Auberge Ravoux now welcomes the traveller with the same unaffected, reassuring façade it showed a century ago. The small entrance, where painters would have stamped the dirt off their boots after a day of painting in the open air, has had countless layers of paint peeled off to reveal the lime-green original, which, according to village elders, was used in the good old days to keep flies away. The staircase leading to the second floor displays, on the landing, a tiny window opening from the restaurant, through which the patron, busy at the counter, could make sure that his customers did not sneak women up to their rooms. And the restaurant itself is a smallish, warm, congenial place, with no-nonsense tables and chairs, bottles of wine and carafes of water straight out of an impressionist canvas, and an all-pervasive aroma of herbs and onions like the one that must have greeted Van Gogh’s senses every lunch and dinnertime, that last summer long ago. According to Ravoux’s daughter (whom Van Gogh painted three times and who was still alive in 1950), the meals he was served at the Auberge were typical of the time: “meat, vegetables, salad, dessert. I don’t remember any culinary pretences of M. Vincent. He never sent a dish back. He was not a difficult boarder.”

If the Auberge today is a memorial to the great dead artist, then all of Auvers is a town of memorials. Not only the small museums, the painters’ lodgings, the names scattered here and there on street signs, parks and cafés, but the landscape itself that lies like a blueprint of certain of Van Gogh’s canvases, evidence of the truth he tried so desperately to capture. Fittingly, it is around the village cemetery that this landscape is best preserved: the trees bend with the vibrant curves of his brushstrokes, the clouds mirror the clouds in his electric skies, the cornfields seem to have remained untilled since the afternoon when he last painted them, menaced by crows and an advancing storm. Any visitor to Auvers who has looked carefully at a Van Gogh painting cannot doubt Oscar Wilde’s dictum, that nature imitates art. The cemetery is quietly moving. Surrounded by a stone wall, the square enclosure set up centuries ago to guard the earthly remains of departed villagers is now visited mainly by Van Gogh’s admirers, who place flowers, letters, poems and all kinds of offerings on his discreet tomb and on that of his brother Theo, who died six months after him and whose body was transferred here, following his widow’s wishes, a few years later. This seems a good place to begin a pilgrimage: at the end.

It was here that, on July 30, 1890, a small group of friends surrounded Theo as the body of his brother was lowered into the grave. Earlier that day, the coffin had been laid out at the Café de la Gare. Dr. Gachet, as a final homage to the artist who had revealed to the world its true nature, surrounded the coffin with sunflowers and with his patient’s canvases. There were many: Van Gogh, kept from starvation by his brother’s small allowance, had hardly been able to give them away for free, and had managed to sell only one single painting during his entire life. Almost a century later, with perverse irony, Van Gogh’s

would be sold for close to £25 million at Christie’s in London.

At a short distance from the cemetery, overlooking the village itself, is the church of Auvers. Because Van Gogh was a Protestant and had committed suicide, his wake did not take place inside the building he had painted so lovingly. Looking at it today, one sees that Van Gogh’s vision superimposes itself on the straight lines and ochre hues of the stone, lending it colours and a movement that we might not perceive without his aid. Describing the painting (now in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris), Van Gogh wrote to his sister that he thought its colour was “more expressive, more sumptuous” than in his earlier sketches of other buildings. It is that sumptuous expressiveness that now overwhelms the viewer standing in front of what would otherwise appear as a quite ordinary French country church.

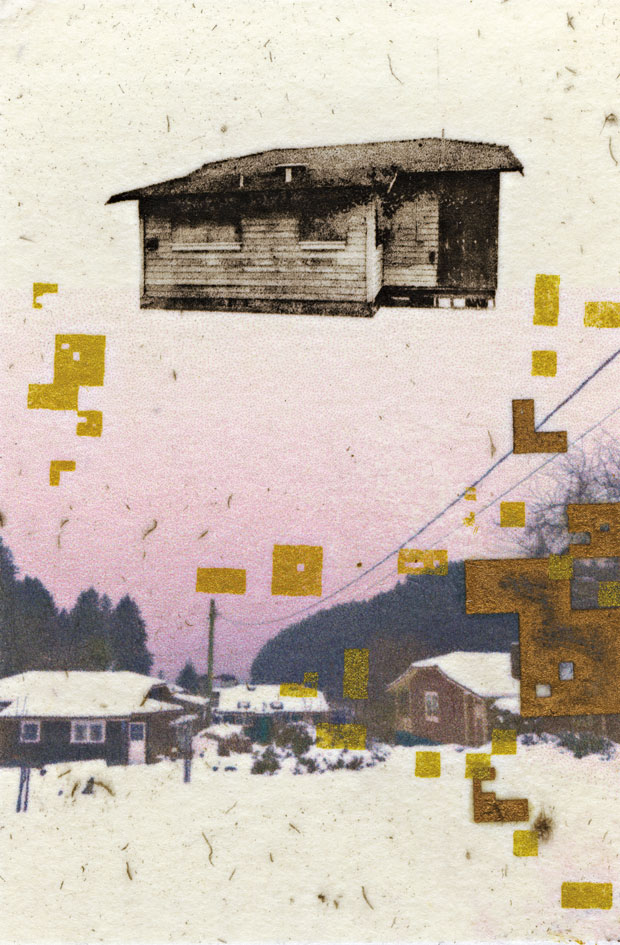

Cemetery, church, the town itself with its winding streets, shaded lanes and lush riverbank offer a pleasant confusion between past and present. With the exception perhaps of the seventeenth-century castle (an imposing recently renovated confection that tries to attract tourists by providing a Disneyfied audiovisual “Journey to the Age of the Impressionists”), all of Auvers is a something of a time machine, transporting the visitor to a moment in which a group of painters seem suddenly to have rediscovered the meaning of colour. Here is the knot of houses behind a now vanished thatched cottage that Van Gogh painted shortly after arriving. Here is the house of the good Dr. Gachet, whose steps bore the tread of most visiting artists. Here is the modest park, now named after Van Gogh, with its uninspired statue of the painter by Zadkine. Here is Daubigny’s studio with its impressive murals by Corot and Daubigny himself. These are landmarks, but it is the village itself that stands as a remembrance of things past, peaceful (in spite of the traffic), uncluttered (in spite of the tourists), full of the particular light Van Gogh sought to reflect in his luminous canvases.

It seems impossible to add a comment to the countless articles, biographies, essays, novels and even songs and films that have been produced in an attempt to explain the work of Van Gogh. What prevented his contemporaries from seeing what we now see, the genius that became so astonishingly clear immediately after his death? What moves viewers from east and west, from all ages and experiences, who look upon his fields and skies and gnarled houses and faces bursting with colour? In one of his letters to Theo, trying to come to terms with the pain of his mental state, Van Gogh wrote: “Madness might be a healthy thing in that one becomes, perhaps, less exclusive.” He could have said more. He could have said that madness (which the Greeks believed was the terrible gift the gods bestowed on their chosen ones) had granted him, through unspeakable suffering, the power to see and love everything, to exclude nothing, and, through his art, to include us all, fellow humans, in his agonizing gift of vision.