The gang of painters who styled themselves the Group of Seven appeared together in public for the first time on May 7, 1920, when they opened an exhibition at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). “We hope to get a show together that will demonstrate the ‘spirit’ of painting in Canada,” explained Arthur Lismer, one of the artists involved, establishing at the outset the ambitious project the Group set for itself. “We are all working to one big end,” said Fred Varley, another member. “We are endeavouring to knock out of us all the preconceived ideas, emptying ourselves of everything except that nature is here in all its greatness and we are here to gather it and understand it . . .”

Subsequently, the legend grew, abetted by members of the Group themselves and their supporters, that the country was not ready for them. “There was plenty of adverse criticism, little of it intelligent,” claimed A.Y. Jackson. In fact, this was not so. For the most part critics liked the show, and the National Gallery in Ottawa purchased three of the canvases and helped to organize a touring exhibition in the United States. This was hardly being “attacked on all sides,” as Lawren Harris claimed, and in no time at all the Group was established as Canada’s national school of painters. But the myth of the misunderstood modernists took hold, and for many years it was the standard storyline for understanding the G7.

In retrospect it is easy to mock the “young fogies” of the Group, who so badly wanted to be rebels but, in the context of post- World-War-I modernism, were simply old-fashioned landscape painters. While artists in Europe experimented with all the familiar “isms”—Dadaism, surrealism, futurism, expressionism, cubism—the G7 made paintings that were, in the words of the playwright Merrill Denison, “as Canadian as the North West Mounted Police or an amateur hockey team.” If you want any credit at all for being avant-garde, you don't want to hear yourself compared to a police force.

As well as manufacturing their own myth, the G7 also established a myth about the Canadian identity: that it was inextricably linked to the northern wilderness they painted. The Group arrived on the scene when Canadians were seeking new ways of imagining themselves as a mature, autonomous nation. They were receptive to a group of painters who claimed to find in the northern landscape a distinctive national identity. Arthur Lismer wrote: “Canada was growing up. The war, destructive of life, was yet the turning point in the development of Canada as an entity. Canadians began to realize that they knew little about themselves.” The Group was determined to fill in the blanks.

In Beyond Wilderness: The Group of Seven, Canadian Identity, and Contemporary Art (McGill-Queen’s University Press), editors John O'Brian and Peter White have conducted a reassessment of the Group’s place in Canadian history. Their mammoth book collects articles both old and new, excerpts from books and a stunning array of paintings and photographs, all reflecting in one way or another on the legacy of the G7. It is difficult to convey the variety of their book in a few words, but basically O’Brian and White are asking why there has been such an enduring association between the G7 landscape, and by extension the Canadian landscape generally, and national identity. Why have Canadians been so attached to a “wildercentric” vision of ourselves?

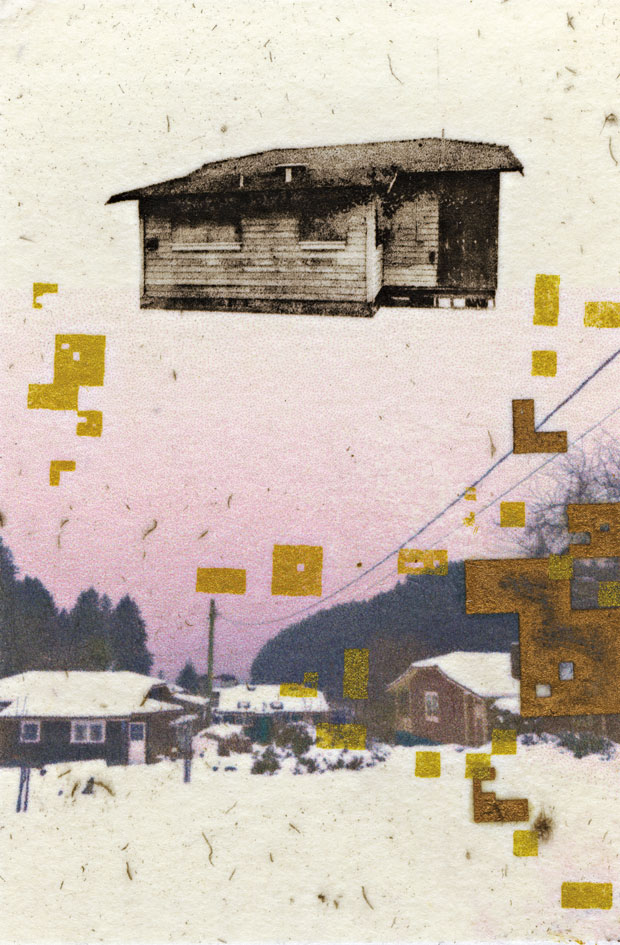

O’Brian and White argue that the G7 “vision” is an inadequate way to describe an urban, multiracial, industrial society like Canada, and pretty much always was. They and their contributors tease out the ideological implications of the long pre-eminence of the Group. In the G7 aesthetic, identity and geography were the same thing. “For them, Canadianness was defined by way of Northernness and wilderness,” write the editors. Meanwhile, the actual inhabitants of the wilderness were ignored, as were the mines and mills that were tearing it apart. The Canada that the Group painted was pristine, untainted by human occupation and industry. O’Brian calls this “painting over” the conflicts that actually divided Canadian society in favour of an idealized, romantic, nationalist vision of the country.

The editors recognize that the G7 view of Canada has lost its hegemony. Banks no longer hang cheap G7 replicas in every branch. G7 paintings are no longer, in Robert Fulford’s memorable phrase, “our national wallpaper.” Still, as John O’Brian writes, “the Canadian fixation on wilderness is not easy to dislodge.” As this fascinating book shows, “wildernicity” remains a defining characteristic of Canadianness. We still think of ourselves as the Great White North, and one of the pleasures in leafing through Beyond Wilderness is to discover how other artists have expanded on or subverted the notion.

Of course, none of this negates the vibrant beauty of the original G7 paintings. But it does remind us that they remain the Group’s true legacy, not the romantic, anti-modern ideology in which they were framed.

.jpg)