In Banff there is nothing to call you away from wherever you are: in Banff you are always already there.

The man driving the bus said to call him Tony, and as the bus rolled out of the airport parkade he announced that he had gone ahead and taught himself the names. His speech was textured with fat diphthongs and skinny vowels that seemed to derive at once from the Australian outback, parts of northern Manitoba and Boston, Massachusetts. He was referring to the villages, towns, rivers, creeks, ponds, lakes, valleys, buttes, peaks and mountain ranges that lay between Calgary and the town of Banff in the Rocky Mountains, whose names he called out enthusiastically as we passed them by, in a narration that lasted two and a half hours, which is how long it took to get to Banff from the Calgary Airport fourteen years ago.

A man near the front of the bus held a video camera pointed out the window for the entire journey. Across the aisle from me, a young woman flipped impassively through a heavy stack of snapshots, lifting each one in turn and snapping it to the bottom of the stack, which was about three inches thick. Eventually she secured the stack with elastic bands and thrust it into a shoulder bag, from which she withdrew another or possibly the same stack and began the procedure again.

From time to time Tony switched to naming the furry mammals that were out there somewhere, he said, but never when we looked out the window: the coyote, the moose, the fox, the grizzly bear, the jackrabbit, the lynx, etc. His favourite place name was Kananaskis, which he repeated several times during the journey with great relish in a flourish of dialectal effects. The mountains as we passed beneath them he denoted as vast, beautiful, awesome, sublime, forbidding, terrific, quite a sight: certainly, by implication and example, always to be admired.

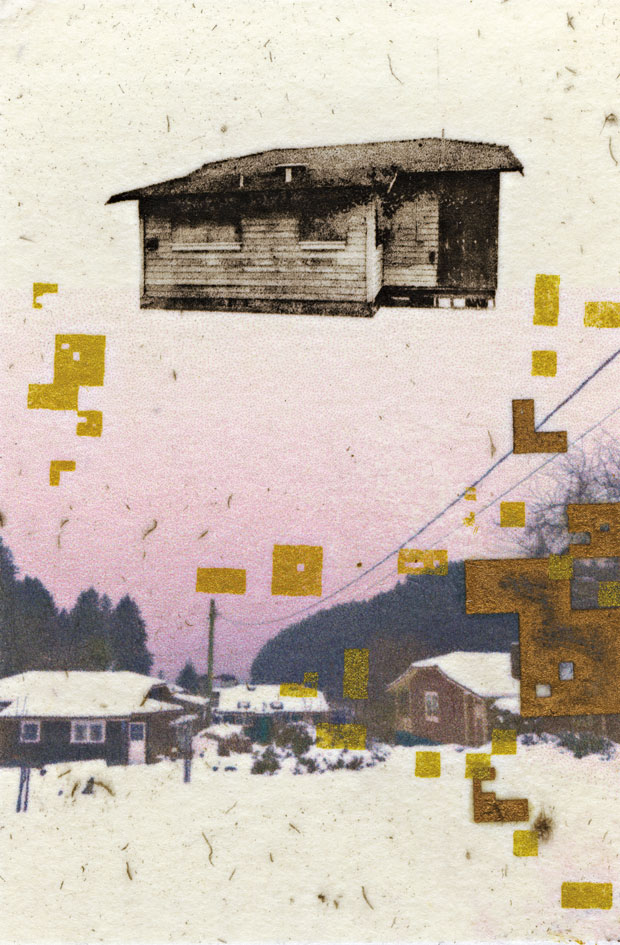

Before leaving home I had been warned by a semiotician friend that Banff had been completely photographed out; indeed my first engagement with Banff, or “Banff,” fourteen years ago, quickly took on the aspect of a billion postcard views. Along the main street lay shopping malls hidden behind rusticated facades; the whole was set against a backdrop of rugged mountain peaks resembling nothing more than enormous photographs of themselves, with bits of cloud and sky near the top. The Banff Centre for the Arts, a construction site offering accommodation for artists, lay nestled in the scenery from which legions of squirrels had been driven by the ear-splitting squeals of trucks and bulldozers backing up eight hours a day.

It was hard to concentrate on anything at the Centre for the Arts that summer, except perhaps on the scenery, an activity for which instruction came in many forms. A photographer’s guide to Banff found on the internet identified “several strategies you can use,” such as getting up early to photograph moose feeding in the marshes, and then taking the gondola up Sulphur Mountain “for outstanding aerial views” (but not too late in the day, “as the mountain casts a shadow on the valley and the views will have flat lighting”). Several mountains offered altitudinous photographers “excellent tripod platforms for views of the valley and townsite.” Point of view, it was clear from the outset, was of the essence at Banff, where even the mountains with their tripod platforms have a part to play in a general scheme of surveillance and replication.

The streets of Banff had been named for the furry mammals that Tony had invoked on the bus: coyote, fox, marten, caribou; it was impossible to set up a mnemonics of difference, so that one was always on the verge of being lost in a tiny village. Not that it mattered: scenery viewing, the central activity assigned to visitors in Banff, is carried out anywhere and everywhere, with the opportunity or the obligation not only to view the scenery but to admire it, and of course to take its picture.

Along the roads leading to the Centre for the Arts were many cleared sections offering views across the valley toward the Banff Springs Hotel, whose souvenir facade of dormers and turrets, celebrated around the world in picture postcards and photo-chinaware, has become so much a part of the universal sea of images that there is no difference between seeing it and remembering it. I had discovered that carrying a camera in Banff was a way to blend in, to become, in a manner of speaking, invisible, and I carried my camera around my neck everywhere I went. Whenever the Banff Springs Hotel came into view, as it did several times a day, I resisted its attractive power by refusing to raise my camera toward it—until one afternoon when I encountered a Japanese wedding party in formal dress arranged at the side of the road. They were equipped with cameras and tripods; in the distance lay the Banff Springs Hotel in its mountainous cradle, and in the foreground stood the bride in her shimmering gown. I raised my camera toward them, toward her and toward the Banff Springs Hotel. No one objected; indeed, we seemed to be co-operating in a scene within the scenery. The wedding party knew precisely what to do with scenery, and they had travelled a long way to do it.

Later that day I watched a man and a woman approach from across the main street. They were holding hands and neither of them seemed to be carrying a camera. When they reached the median, the man turned his head and glanced up the street toward Mount Norquay looming in the distance; he shrugged an elbow and an enormous camera appeared in his hand; he fixed it on the mountain and snapped the shutter and then, with another shrug, the camera was gone, into the depths of his shirt. I had witnessed a spectacular example of the snapshot: the photograph taken by reflex before the subject, in this case a mountain, can escape the photographer’s attention.

I returned to Banff last February to attend a writers’ conference, and this time the bus driver was silent for the whole journey, which was half an hour shorter than it had been fourteen years ago, which led me to wonder if sections of the highway had been straightened out during my absence. Many passengers wore earphones and passed the time slouched down looking into Blackberrys, iPods and other digital devices. It was possible to imagine that they were listening to the original Tony reciting place names, or even watching the video that the man at the front of the bus had made fourteen years ago. From time to time a digital device would appear at window level above a seatback to record an image of the passing scene.

The Banff Centre had grown into a much larger construction site over the years and had dropped “for the Arts” from its name; now it was merely a Centre. Heavy machines were much in evidence and the squeal of backing-up signals still filled the air. Occasional squirrels scampered over lawns and into the underbrush, but never more than one squirrel at a time; I realized later that there may be only a single squirrel at the Banff Centre, appearing here and there again and again to represent his exiled species. The walls of the reception hall were hung with handsome black-and-white photographs of nearby mountains the originals of which were in the usual places, available for viewing and for being viewed from.

The writers’ conference went on for three days of talks, from morning to night: readings, performances, presentations, plenary sessions. The schedule was not as burdensome as it might have been elsewhere, for in Banff there is nothing to call you away from wherever you are: in Banff you are always already there. In the intervals, attendees milled about amiably in the open spaces not occupied by heavy machinery, always within the purview of the mountainous tripod platforms looming over us. Name tags that we hung from our necks on cords identified us as belonging to the crowd of (for me at least) strangers from distant parts.

Several of the presenters were self-described avant-gardists who generated poetry and other texts by arcane procedures that included computation, cutting, pasting, counting, copying out transcripts of news reports and reading them aloud, hypertext, translation and mistranslation, textile-making, sound generation, dance and movie-making. Appropriation, constraints, rule-making strategies and rigorous techniques were much in play, along with elements of subversion, transgression, iteration and the pleasures of repetition. Presenters adopted a particular style when discussing matters of theory and technique: voices dropped from conversational registers into flattened monotones, the rate of delivery accelerated and the language tended to thicken under the weight of too much jargon. During one such presentation, a volunteer from the book table said to me, you know, none of us understand a thing of what these people are saying. I assured her that understanding was not required in the avant-garde.

The author of Eunoia described a plan to embed or implant a poem encoded in the language of recombinant DNA into the bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans, a name that he pronounced fiercely, frequently and at daunting speed. He had taught himself genetics, he said, and later he said that he was a self-taught geneticist. The bacterium in question, which he referred to in the diminutive as radiodurans, is expected to outlast the solar system, the galaxy and whatever else there is to outlast, with the result that the poem encoded within its DNA—which, I recall him saying, would at some point during its five-billion-year duration generate a new poem, also in the language of DNA—would be the oldest poem in the universe.

Now here was a challenge not only for the genetically minded in the avant- garde but for the theologists in the audience, the ontologists, epistemologists and any who are drawn to the problem of how what is known can be said to be known. Was it not, after all, just as likely that the DNA poem, once encoded and embedded, would already be the oldest poem in the universe, even “before” the end of all things? There was silence in the large hall, and only a few desultory questions were put by audience members, many of whom seemed like me to be dazzled or stunned by the implicit challenge of having to grasp not only a point of view but the point of view of the point of view as well, to have to go deep, to descend far beneath the beguiling surface of things, to where, or when, after and before are equally extinct, and all is of a frightening sameness.

Banff, the place, the concept, the arts haven, the collection of scenic views, all devolve from computations set into play in the nineteenth century, in Ottawa, Montreal, Toronto and London, England, constrained by capital, geography and the politics of Empire; its techniques and procedures extended to appropriations of prairie, river, mountains and valleys; to subversions and transgressions—of rights, possession and habitat; and to vast iterations on many scales: shovels, spikes, sticks of dynamite, rail sections, rail cars, indentured labour, personnel, etc.; and finally the ultimate iteration of the paying passenger, repeating again and again the singular journey to Banff and the courtyard of the Banff Springs Hotel, where Cornelius Van Horne, genius, prime mover, president and first passenger of the railway, is memorialized in bronze, in full life size on a pedestal from which his effigy extends an arm and a forefinger, pointing up and away, toward the tripod viewing platforms in the distance. His was the final pleasure of repetition, the repetition of dollars in his pocket, the repetition of knick-knacks in his castle: he is the poem encoded in the stones of the Rocky Mountains 125 years ago, the beginning and one of the ends of a certain history.

“There is only one limit beyond which things cannot go,” wrote Walter Benjamin in 1926: “annihilation.”