Last month in Calgary a friend showed me the way to Louise Bridge by sketching a map with her fingertip on the dust jacket of The Wolf King, a book by Judd Palmer that we had been admiring at her kitchen table. A day later, with the afterimage of my friend’s map as a guide, I went straight from my hotel to 10th Street where it hits the Bow River in order to observe in twilight the understated beauty of Louise Bridge, with its arches described as flattened and softened, like the breasts of a woman reclining, by Louis de Bernieres in a soliloquy written nine years ago, and in which the river ice reminds him of marzipan chunks dusted with sugar and slabs of decaying brie strewn on a discount counter.

I clambered down a hill covered with snow and exposed a few frames of film to the silhouette of Louise Bridge stretching out past slabs of ice along the shore and the black water, and as I walked along the pathway beside the river I was able to observe Louise Bridge recede into darkness and the afterlight of the setting sun. Eventually I headed back downtown with the image of my friend’s map still in my head, determined to veer over to Chinatown to get some dinner, and that was when the map, or my extrapolation of it, began to fail me in the growing darkness. I walked for more than an hour, triangulating my way through an area of the downtown fringe that by my reckoning should have contained Chinatown, and I recognized buildings that I had seen only a day earlier, adjacent to or at least very near Chinatown, among them a collection of restored shops and warehouses, and the YWCA, but the Chinese Cultural Centre and the little row of Chinese restaurants that I knew to be close by were concealed by dark empty spaces.

It might be supposed that I was lost, but the tall buildings of Calgary that crowd the downtown quarter never left my peripheral vision. Few Calgarians were in evidence: a couple of joggers and lone pedestrians and couples getting in and out of cars, all of them seeming to know the parts they had to play in their city, which was noticeably clean and reasonably well lighted (except for the streets of Chinatown, wherever they were), and the iron grates in the sidewalks had been fitted with iron footpads, perhaps to encourage pedestrians to walk on them without worrying about falling through. I did not wish to reveal myself as a person who had lost the way to Chinatown; I spoke to no one.

In the end, I struck out along an avenue or a street, knowing that if I came upon 7th and 7th, or 8th and 8th, etc., according to the system of Calgary streets, I would be near my hotel. Eventually such an intersection appeared, and as I came up behind the hotel, tired and hungry and rather dispirited, I spotted the Chinese restaurant that I had noticed and then forgotten on my first day in Calgary, and so I went in and ordered the ginger beef, wonton soup, fried rice and veggies.

I had arrived in Calgary intending to seek out the CPR Irrigation Ditch, the artificial landform mocked by Bob Edwards in 1906 in the pages of the Calgary Eye-Opener, but whenever I was in the company of Calgarians I failed to inquire for directions, or even to ask if the Irrigation Ditch still existed. Calgary had been home to the Social Credit Party and the Prophetic Bible Institute, and it should be no surprise that an outsider would be thinking of those once powerful and now defunct institutions while strolling down an outdoor mall lined with department stores and boutiques, as I was, when a blizzard erupted in the street and a bitter wind filled the air with tiny snowflakes. An angry man on the sidewalk began to curse as the tempest swept over him. “God damn, it’s snowing. God damn,” he said, and vanished into the whiteout. In another moment the blizzard melted away to reveal the sun in a deep blue sky, and from the window display in Sears department store, where I stopped to brush the snow from my shoulders, the image of William Aberhart, founder of the Social Credit Party and the Prophetic Bible Insititute, was peering down at me: here was all that remained of the Prophetic Bible Institute, on display in a vitrine: the tops of two newel posts taken from the main staircase, and a photograph of the congregation wearing heavy overcoats in 1936. The tops of the newel posts were egg-shaped and the colour of old cedar; the geometric pattern worked into them had been worn almost flat by the passing of hands, and time.

Twice in Calgary I was asked by serving staff in restaurants if my meal “tasted all right,” a usage new to me and rather unsettling. A few days later in Winnipeg, I was asked the same question as I ate the chicken entree in the hotel restaurant; and then in a sandwich place on Portage Avenue, where I stopped for a bowl of soup, a serious young woman said to me: “Is your food tasting okay today, sir?” In Winnipeg the snow had melted and frozen again several times, and the sidewalks were lumpy and hard to walk on.

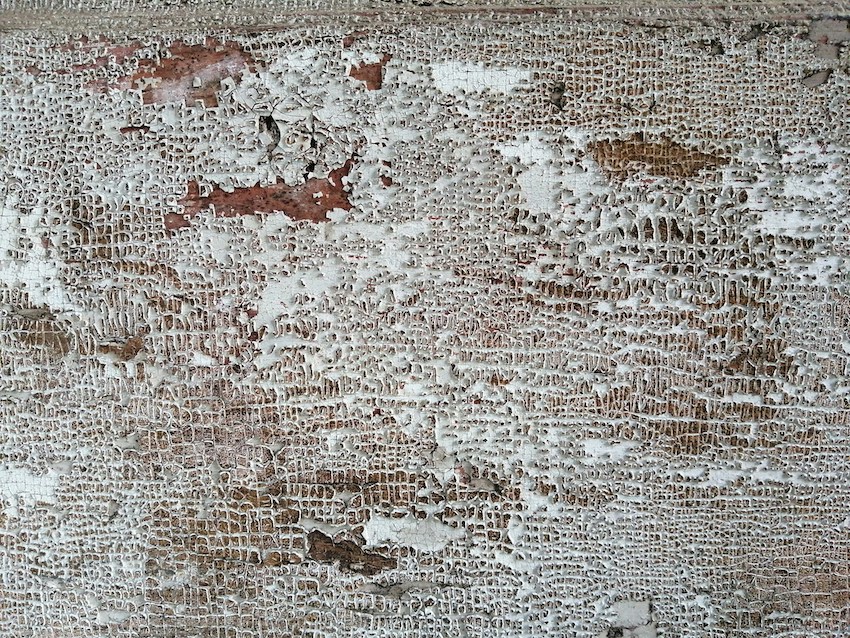

One afternoon I lost my way, and when I found it again my ankles were sore from crunching along endless icy pathways through old neighbourhoods covered in snow. Winnipeg was much grittier than Calgary: it seemed to have been decaying slowly for a long time, while managing to retain a certain dignity in the faded storefronts, disused office buildings and empty warehouses. There were no footpads on the iron gratings in the sidewalks, and there were more people in the streets, and some of the streets cut away along interesting diagonals, and there were fewer tall buildings crowding the sidewalks. The people I observed on foot and in their cars seemed manifestly to be Winnipeggers, although I could infer nothing from that perception (drivers who stop at intersections and look in your direction); I was explicitly aware of not being a Winnipegger myself, of being a stranger in fact arrived only recently from Calgary, where I had also been a stranger.

History in Winnipeg seems to begin and end with World War I, evidence of which is everywhere in street names and monuments, and in the snow-covered grounds of the legislative building (on the roof of which a granite sphinx overlooks the grounds). The intersection of Portage and Main, famous for its winds and its temple banks, perhaps as a side effect of civic retrenchment, has come to resemble a leftover piece of No Man’s Land: the sidewalks have been barricaded with concrete parapets, and only the foolhardy or the suicidal would climb over them and thrust out into the traffic under the eyes of the bronze infantryman looming up before a wall of imaginary snow-covered sandbags in front of the Bank of Montreal.

At a bus stop along Main, two small boys in parkas were kicking with their boots at piles of dirty snow and ice heaped up along the curb, while their mother, who was puffing on a cigarette, kept an eye out for the bus. In the distance could be heard the low rumble of freight trains. That night behind the hotel, a young woman in baby-doll pajamas ran into the intersection holding a pack of cigarettes in her hand, and a man leaning up against the wall said, “Hey, some of these girls are real crazy.” He too was puffing on a cigarette; I took him to be a Winnipegger. I went into a place called Mitzi’s Homemade Chicken Fingers and ate chicken fingers and mushrooms and asparagus tips and rice at the only table not occupied by families and young couples and even tiny babies, all intent on eating chicken fingers and French fries and having a good time on a Saturday night, which was what I began to do as well, in my role as a stranger in town surrounded by Winnipeggers.