.svg)

In 193 André Breton outrageously suggested that “the simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down into the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd.” He meant the action to exist only in the sphere of the unrestrained imagination. He was writing about literature; reality co-opted his writing.

I meet Mavis Gallant at La Rotonde for coffee. She tells me how struck she was last year by the French need to show sympathy for America, and how anyone with the slightest “American” accent (Canadian, Australian or whatever) received condolences; she felt obliged to accept them graciously. A friend of hers went into a shop in Paris and, having shown herself by her accent to be “American,” was immediately surrounded by well-wishers and sympathizers, only to discover, minutes later, that her credit card had been pinched.

History, in our eyes, seems to take place through comparisons. A few days after the tragedy, I heard of someone who had been trapped that morning inside a bookstore close to the World Trade Center. Since there was nothing to do but wait for the dust to settle, he kept on browsing through the books, in the midst of the sirens and the screams. Chateaubriand notes that, during the chaos of the French Revolution, a Breton poet just arrived in Paris asked to be taken on a tour of Versailles. “There are people,” Chateaubriand comments, “who, in the midst of the collapse of empires, visit fountains and gardens.”

Mavis sent a card with something she had forgotten to tell me—how someone described the people throwing themselves out of the towers: “They looked like commas in the sky.”

All day it has been sunny. There are bees flying very low, buzzing around my ankles in the grass. I feel exhausted by the news (the invention of the “war on terrorism,” the justifications for invading Iraq) on our newly acquired television, and by the recapitulations of last year’s events.

We create climates of hatred. During the military dictatorship in Argentina, the loathing and fear felt toward anyone in uniform was palpable. I’ve felt that on different occasions, when visiting Barbados, Iraq, Jerusalem.

Maybe our rulers and our gods must be made to look angry. Julien Green says that, in the eighteenth century in Scotland, the word “wrath” kept coming up so frequently in the pulpit that a certain printer of sermons, having exhausted his provision of

s instead.

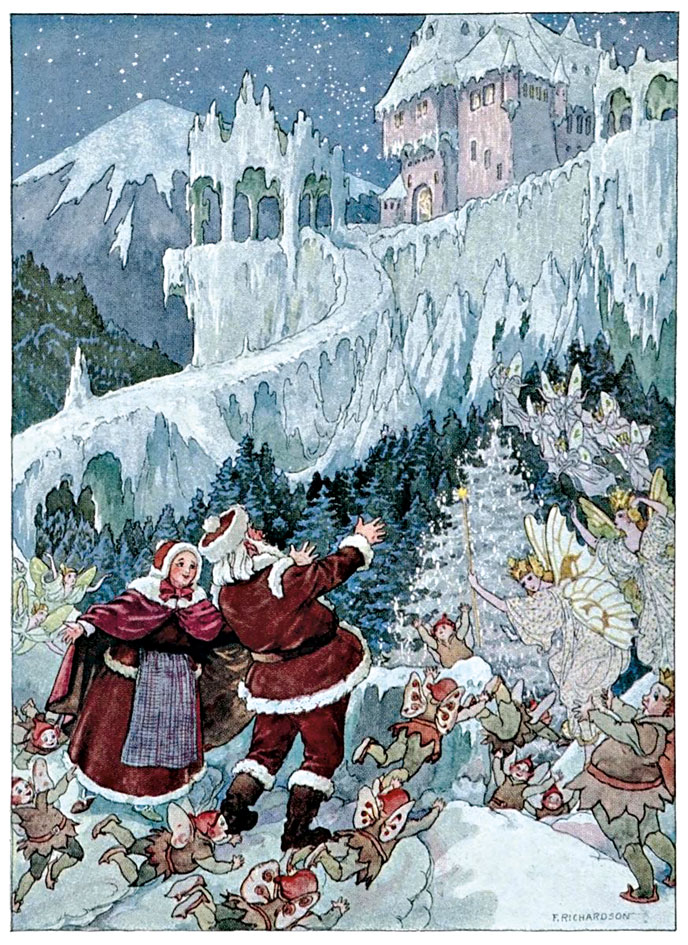

Our god is the god of fairy tales, setting tests for his three sons, each of whom believes himself to be the best-loved, though none is ever truly “the chosen one.”

In Georges Courteline’s

:

“So tell me, you were mentioning God a while ago. Do you know him?”

“Yes and no. I know him in that I’ve heard him mentioned, but we’re not on such intimate terms that we’d play billiards together.”

Chateaubriand assumes that a world has come to an end and that he, a shadow among shadows, will write down what he recalls of its destruction. Perhaps that is all we do: remember. Does all this dredging up of images and words serve a purpose? “The recollections that awaken in my memory overwhelm me with their power and their volume. And yet, what are they for the rest of the world?”

Doris Lessing, commenting on September 11: “Americans felt that they had lost Paradise. They never asked themselves why they thought they had the right to be there in the first place.”

David Wojnarowicz, from “In the Shadow of the American Dream: Soon All This Will Be Picturesque Ruins,” written in 1991: “Americans can’t deal with death unless they own it.”

The ancient Anglo-Saxons allowed Roman buildings to crumble and then wrote elegies to the ruins. Other examples? The correspondence of the illustrious French women of the eighteenth century; the English detective novel of the golden age; Joseph Roth and Sándor Márai; the novels and stories of Mavis Gallant; the

of Sei Shonagon . . . all these attempts to recapture the past have a deep elegiac quality.

For Chateaubriand, the world we see is

memory: of things fleeting, ephemeral, gone and yet unwilling to relinquish us entirely. The past will not go away: what we are experiencing only exists in the moment that goes by.

Chateaubriand tells the story of his sister’s spiritual director, a certain M. Livoret, who on the night of his appointment was visited by the apparition of a certain Count of Châteaubourg. The ghost pursued him everywhere: indoors, in the forests, in the fields. One day, unable to bear it any longer, M. Livoret turned to the ghost and said, “Monsieur de Châteaubourg, please leave me,” to which the ghost answered, “No.”

For us it is the present that is constant; we refuse to let it go. Newscasters take for granted a public infected with forgetfulness, unable to recall what occurred moments earlier; a public in need of the constant ghost of “the event.” Is this our attempt to eliminate mortality? Brief flashes, repetition, a sense of immediacy; we are offered something like a never-ending moment that allows no distance in time or space.

Another definition of Hell: the eternal re-enactment of a deed purged of any possibility of passing.

Chateaubriand: “One thing humbles me: memory is often a quality associated with foolishness; usually it belongs to slow-witted souls whom it renders even slower because of the baggage it loads upon them. And yet, what would we be without memory? We would forget our friendships, our loves, our pleasures, our business; genius would be unable to collect its thoughts; the most affectionate of hearts would lose its tenderness if it did not remember; our existence would be reduced to the successive moments of an endlessly flowing present. There would be no past.”

The last word in Chateaubriand’s

is “eternity.”