A young man acquires a 1957 Pontiac with a big Strato-Flash V8 engine, whose purpose is purely to go—Glenn Gould-style.

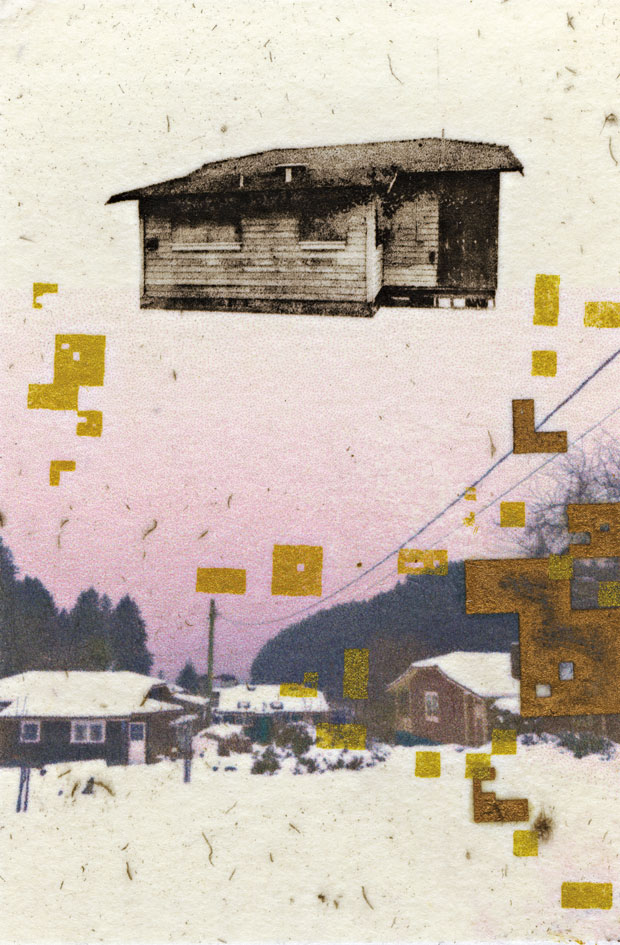

On a Monday afternoon in May I walked out of the Burrard Health Centre after a disquieting session with the ophthalmologist on the fourth floor, with my pupils dilated and my eyes tearing up in the sunlight. As I peered into the street and across to the alley that runs into Burrard Street from Thurlow, I remembered the 1957 Pontiac sedan given to me in the spring of 1972 by Richard B. Simmins, ex-director of the Vancouver Art Gallery, as payment for a spurious debt of twenty-five dollars, and as I waited in front of the Health Centre for my vision to clear I remembered guiding the great bulk of that vehicle, a Pathfinder Deluxe with a Strato-Flash 283 V8 engine, power steering, Turbo-Glide transmission, four-speaker radio, whitewall tires and enormous chrome bumpers, down that same alley from Thurlow into the Friday night traffic on Burrard Street, looking for a place to park.

I had driven the Pontiac over from Chinatown along Pender Street to Thurlow under the guidance of Richard Simmins, who had given me the keys and the registration in the Delightful Foods Cafe; I dropped him at the Felix Apartments on Melville before setting out as, as Richard Simmins put it, the operator of a bona fide land yacht of my own. My intention was to leave the Pontiac in the street near the Windermere Apartments on Thurlow, where I was living, and go down to the beer parlour on foot, but it was early Friday night and there was nowhere to park, at least no space big enough in my estimation to squeeze the Pontiac into: my parking experience at the time was limited to Volkswagen Beetles, Morris Minors and a 1952 Studebaker with no reverse gear.

After circling the block I turned into the alley beside the Windermere, rolled down to Burrard Street and made the right turn across from the Health Centre, where I was now standing at three o’clock in the afternoon waiting for my eyes to clear; I let the Pontiac take me over to Davie Street and the left turn down the hill and across Granville Street and into the parking lot behind the Cecil Hotel beer parlour, where, when the Pontiac had come to a halt between the white lines on the asphalt, I slipped the big gearshift on the steering column into P for Park, as instructed earlier by Richard Simmins, jammed on the emergency brake with my left foot, turned off the lights, switched off the radio and rolled up the window. Then I went into the Cecil through the back door, to let my friends know of my strange good fortune.

Richard B. Simmins was my father’s age, a secretive man given to tweed jackets and corduroy trousers. The Delightful Foods Cafe was his favourite restaurant, brightly lit as I remember it, and filled with patrons speaking quietly at tables with Formica tops and chrome trim amid the clang of pots and pans and loud talk emanating from the kitchen, where men and women and at least two children often seemed to be arguing fiercely. We ate fried noodles and prawns in black bean sauce and slices of barbecued pork dipped in hot mustard, and pickled cabbage and bamboo shoots, and more small dishes ordered in a whisper by the man who had taught me among other things how to cook a bratwurst sausage in a frying pan in a quarter inch of water. His goatee and moustache were always beautifully trimmed; a friend once asked me for an introduction to Richard Simmins so that he might obtain advice on growing a beard of his own. Often at these meetings in the Delightful Foods Cafe Richard Simmins had an announcement to make, or a confidence to share—intended, it seemed to me, perhaps unfairly, to thicken the aura of mystery about his person. On this Friday evening in 1972, he spoke at length of his admiration for Glenn Gould, the classical pianist whom he may or may not have known as a friend, and about whom I knew nothing at all. Glenn Gould, besides being one of the great pianists of the world, Richard Simmins said, liked to cruise the highways of northern Ontario alone in his Lincoln Continental while listening to pop music on the radio, a pastime, Richard Simmins said, in complete confidence, that he himself had taken up, in the 1957 Pontiac with the Strato-Flash V8 that he had acquired in emulation of the much wealthier Glenn Gould, and for months now Richard Simmins had been driving out of the city on his own, he said, along the secondary highways up to Squamish, Pemberton and Lillooet and through the Fraser Canyon to Spuzzum, Yale, Spences Bridge and Boston Bar.

As we neared the end of our meal, he changed the subject to an old debt of twenty-five dollars that he had claimed to owe me from time to time, and of which I had no memory; and there may have been favours that I had done for Richard Simmins that I have forgotten now; in the event, the keys to the Pontiac appeared on the table and in another moment I was the owner of the 1957 Pontiac with the Strato-Flash V8 and the fourspeaker radio, and inheritor of the spirit of the great Glenn Gould.

I left the Cecil beer parlour at closing time and waited in the Pontiac for the last drinkers to clear the parking lot before switching on and rolling out to Davie Street, and then instead of driving back to the Windermere I swung left onto Granville Street and powered up onto the Granville Bridge and over the bridge to the intersection at Broadway, made the left turn and crawled along for a couple of blocks to Denny’s, the twenty-four-hour diner where my friends at the Cecil had said they planned to meet after the beer parlour closed; I spun the wheel and let the Pontiac roll smoothly over the curb into the parking lot, slipped it into Park, set the brake and switched off the ignition.

It was three o’clock in the morning when I got back into the Pontiac and applied the Simmins procedure for the third time: ignition, lights, brake, transmission, gas pedal. Again the Pontiac shivered into life and began to roll, backward a half turn, then forward to the sidewalk, where I halted to wait for a pedestrian to pass, a woman alone and unsteady on her feet, who faltered as she stepped into the headlights and put a hand onto the hood of the Pontiac. She was dressed in a black jacket and jeans; she held the other hand up to the side of her face; she may have been drunk, but when I got out of the car I could see that she had been beaten up. I remember glancing over my shoulder as if expecting something or someone to be there, along that bleak stretch of Broadway illuminated by the lurid neon of the BOWMAC car dealership and the fluorescence leaking from the windows of Denny’s, but there was no one, no ambulance, no police car, no assailant in sight.

I opened the passenger door and she got in, and I closed the door and went around to the driver’s side and slipped the Pontiac into Drive. We swung left onto Broadway and I touched the gas pedal and in another moment we were rolling down Granville Street back the way I had come, over the bridge to Davie and then left up to St. Paul’s Hospital on Burrard, across the alley from the Windermere Apartments. I pulled over near the Emergency entrance to prepare for the U-turn in the parking bay. I’ll take you in here, I said to my passenger, who had been silent the whole time. Now she was shaking her head and I had to lean over to hear her. I have to go home, she said. Can you take me home, please. I could see only the side of her face; she turned toward me and lifted her hand to reveal a smashed cheek, a swollen eye, a broken lip: she had been wounded. No hospital, please, she said. She lived in North Vancouver, on the Reserve, she said, which was a long drive away, half an hour through Stanley Park and over Lions Gate Bridge; any misgiving I felt was countered instantly, I remember clearly, by the mere fact of the Pontiac itself, so recently acquired, and the purpose of which was purely to go somewhere, to go.

We continued down Burrard and took the left onto Georgia and cruised through the intersections at 29 miles per hour; once onto the causeway through Stanley Park, I felt something like the open road calling as we swept along under the shadow of the big first flickering in the chemical light of the street lamps, and then a hint of what eight cylinders can do as we powered over the big span of Lions Gate Bridge across Burrard Inlet; we made another two miles along Marine Drive and I took the left fork away from the ocean and told my passenger that I couldn’t take her home without checking in at a hospital, Lions Gate Hospital, up the hill from the Reserve. I know people there, I said, and I told her that I would wait for her. She didn’t protest, and when we pulled into the driveway at Emergency and stopped the car it was clear that she was in pain; I tried to ease her way into the hospital and into the wheelchair provided by an attentive nurse. Another nurse, or perhaps an attendant, took down what details I could give her and seemed confused when I explained that I didn’t know the injured woman. She went away and came back and told me that I ought to take my passenger back over the bridge to a hospital downtown. I refused. At some point a Mountie came into the ward and wanted to know why I had picked up this woman at such a late hour and brought her such a long way. Finally I told the nurses behind the counter that my father was the chief surgeon at Lions Gate Hospital, a confession that I would have preferred not to make, and that if they did not attend to the injured woman, I would call my father and get him down here to do it himself.

I was left alone on a bench for an hour or two hours; I had a copy of City Life by Donald Barthelme, which I recall reading all the way through in the waiting room of Lions Gate Hospital as I waited for news of my passenger. And then one of the nurses appeared and said that my friend was asking for me. They had found a bed for her for the night, she said. She took me down the hall and into a small room in which the woman lay in bed under immaculate white sheets. Her face was partially bandaged and she was quite beautiful as she managed a crooked smile and put her hand out to me. I stood there for a while holding her hand. She was very handsome, with her hair spread out over the white pillow. I would like to know you, she said.

When I powered up the Pontiac for the last time there was light in the east and the night was beginning to vanish. I had the radio on, and something on the hit parade was playing and I had the window open. When I crossed back over Lions Gate Bridge, I swung off the causeway onto Stanley Park Drive, a narrow paved road through the forest, and motored on past Prospect Point, Third Beach, Siwash Rock, the Hollow Tree, Ferguson Point Tea Room, the grave of Pauline Johnson, Second Beach and finally the tennis courts and English Bay. I could hear birds. I don’t recall thinking about Glenn Gould. The Pontiac shot smoothly up the hill on Davie Street and soon I was back where I had started, looking for a place to park near the Windermere on Thurlow Street.

During the drive to the hospital I had asked my passenger her name; she told me but I have forgotten it. I told her that I had just acquired the Pontiac and that this was the first time I would be taking it over Lions Gate Bridge. I recall her saying to me in a whisper, “Indians like Pontiacs,” and nothing else as we drove through the night.