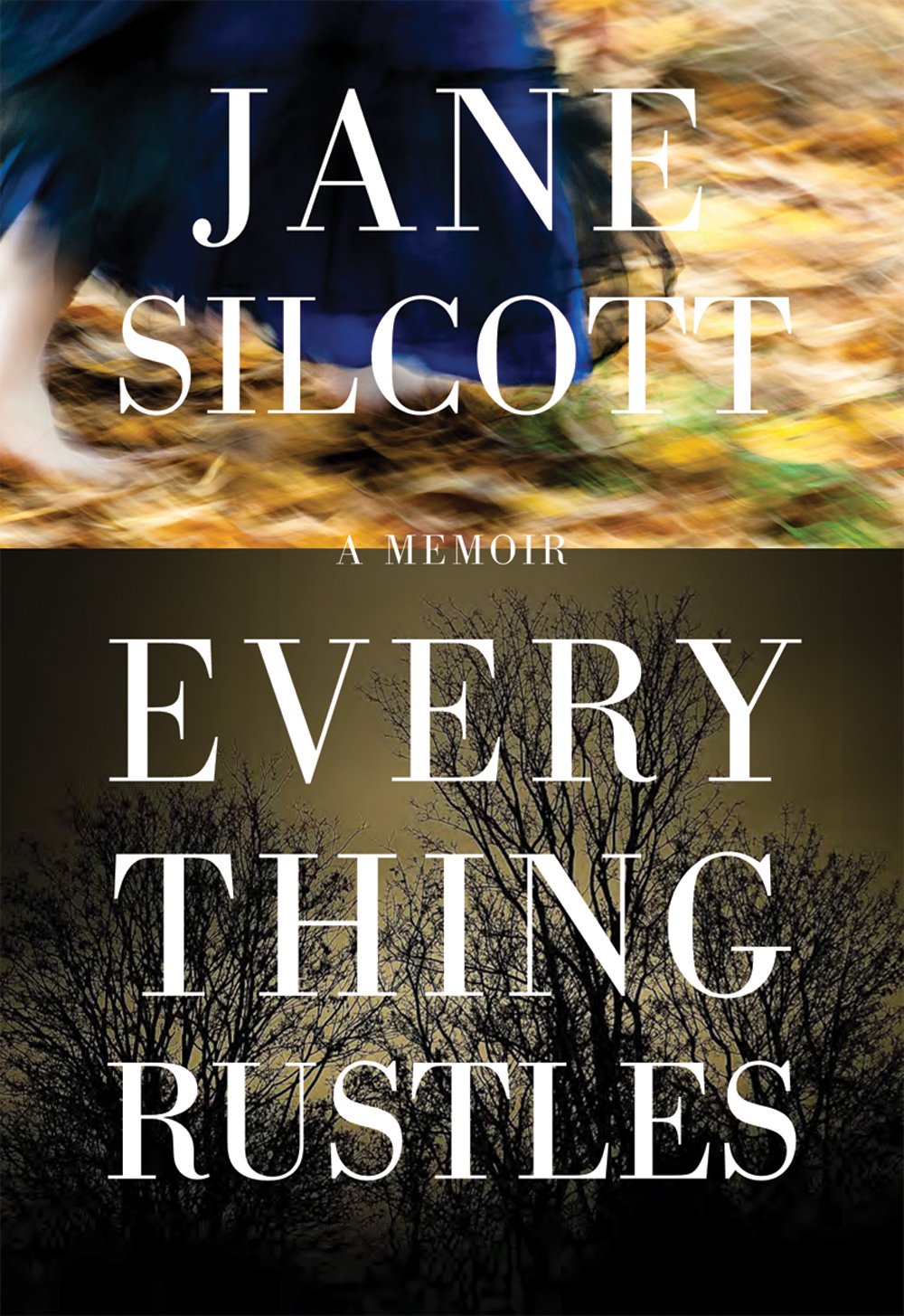

Full disclosure: I’ve chatted socially with Jane Silcott several times and have followed her writing in Geist with interest and enthusiasm. Several of those Geist pieces appear in Everything Rustles: Memoirs (Anvil Press), Silcott’s first collection of personal essays, which was a finalist for the Hubert Evans Non-Fiction Prize in 2014. In Everything Rustles Silcott writes of the happenstances and hazards of ordinary life: middle age, marriage, loss, love, and laundry rooms; the quotidian events that snag at the consciousness of an intelligent observer, proving that every life gives opportunities for reflection and deeper insight. She draws upon the circumstances of her own life to probe the tender points of the human psyche, and does not shy away from revealing her yearnings and disappointments. The writing is honest and direct, the tone shifting between levity and melancholy: “My aging friends and I sometimes sigh over the loss of our youth, of being attractive just for being young and female. We watch men walk past, then joke about our easy hearts, which sway and lean, following the good hard scent of them, the beauty of their muscled legs and easy laughs, the dark notes in their voices and the potential flare of sex in their eyes.” To me Silcott is extraordinarily brave, in the sense that bravery —or a form of bravery—is required before one can face and accept the humbling consequences of “careening toward age, hurtling on a downward slope” to one’s inevitable end. Thanks to the prize-winning essay “The Goddess of Light & Dark,” which draws upon Silcott’s experiences as a clinical teaching associate at BC Women’s Hospital, I now know more than I ever thought I would about the rituals and revelations of a pelvic exam—and am (I think) a better person for it. After reading that essay and the thirty others in Everything Rustles, I think it fair to say that I now know Jane—aspects of Jane—better than I know any of my closest female friends.

Christine Lowther lives on a floating home she’s named Gratitude, a “blue, barn-shaped cabin” moored in Clayoquot Sound, a 90-minute commute by kayak (“twenty minutes in a barnacle infested motorboat”) to Tofino where she works several day-jobs, including one at a local gallery and another at Tofino General Hospital. From her bed on Gratitude she can see Lone Cone Mountain on Meares Island; from her front porch she can slip into the waters of Clayoquot Sound for a night swim: “Scissoring my arms and legs I make angels with the ocean’s bioluminescence, comet-trails streaming between my fingers.” Lowther is a gifted poet with three collections to her credit, and has co-edited two collections of essays from BC’s “far west” coast. Born Out of This (Caitlin Press) is Lowther’s first book of prose, “a mixture of autobiography, nature writing, humour, activism and punk.” In the powerful essay “Gifts From Lands So Far Apart” Lowther explores the tragic circumstances surrounding the murder by her father of her mother, the celebrated poet Pat Lowther, when Christine herself was not yet eight years old. Environmental activism is what brought Lowther to the southwest coast of Vancouver Island in 1991, one of those who were protesting against the logging of old-growth forest in the Walbran Valley, and many of the essays in Born Out of This address ecological issues and activism. While not exactly a “how to” book for those wanting to live a creative, ethically honorable life on the continental margin, Born Out of This will feed such dreams, proving that there are alternatives to the concrete and glass canyons of our urban centres, and their ever-metastasizing suburbs.