Ilonka, my host in Berlin, claims not to be a “German” or a “Berliner”: if anything, she said to me at dinner in the Kastanie restaurant near her flat, she is a member of the Kiez, her neighbourhood in the Charlottenburg district. She looked around the outdoor patio where we were sitting and said, A lot of these people are regulars and there is one man, for instance, who comes here every day; he uses the Kastanie as an office with his laptop and sits here for hours. Everyone knows him.

Ilonka grew up in a West Berlin suburb in the 1970s and ’80s, when the city was still divided and West Berlin was surrounded by the Wall. She travelled out of Berlin often with her family, to the North Sea, which she loved, and to the countryside, and it was no big deal crossing through East Germany except for being frisked at border crossings and forced to exchange West for East marks at par. She took Berlin to be her home, took it as factual and not tragic that Russian and American symbols were all over the city, and only lamented sometimes that she lived in a suburb—not of course in the North American sense, but in the European sense, where the dwellings are four- and five-storey row houses fronting directly on the street. Her family travelled to West Germany as well, via the railway corridor that sealed them off from the East German republic.

Earlier in the day we had walked through Treptow Park and viewed the massive Soviet monument to the defeat of Fascism and the liberation of Berlin, rendered in the monumentalist style of socialist realism, a good six storeys high. It depicts a youthful Russian soldier holding a child with one arm and a gigantic sword in the other hand, which he points down toward the shattered swastika beneath his enormous boot. The plinth is as high as a house. The statue is larger than anything you’d want to have in your town and larger than what few cities besides Berlin could contain without embarrassment or a severe sense of oppression. Ilonka explained that Berliners in general see little problem with such monuments: Soviet President Gorbachev had insisted, as part of the agreement to open the Wall, that the monuments be kept and maintained by the German government, as they are part of the city’s identity, just like the Brandenburg Gate or Checkpoint Charlie or the Reichstag. Skateboarders, she said, delight in using the monument’s great stone surfaces, some of which are gently sloped, while others have stairs and stone banisters perfectly spaced and tiered for skateboard action. For lower-income Berliners, Treptow Park, with its grassy expanses, its lake and its patches of forest, is a favoured setting for summer outings. As we walked I noted that the graffiti, ubiquitous in Berlin, are somewhat subdued here: they share stone surfaces with a sequence of Soviet realist bas-reliefs of workers and soldiers overcoming Nazi might that lines the promenade leading up to the statue.

En route to Treptow Park, Ilonka took me first to the Jü discher Friedhof, one of Europe’s largest Jewish cemeteries and one, surprisingly, not destroyed by the Nazis. The first thing I noticed after walking through the mock-moorish style gate and administration complex was the size of the gravesites and mausoleums. They looked like scaled-down mansions and gardens. Many had walk-in-style facades of black marble or polished granite, complete with pillars and friezes, and the plots around them were arranged in the classical French garden style. Many sites were being rebuilt: before one of them, a woman had set up a tripod and was photographing the reconstruction details: the relationship between the stone, earth and plants, and the tools used to link them into a coherent whole.

The second thing that struck me was the names on the tombs. I had always thought, while growing up in small-town Canada, that names like Cohen, Schlesinger, Rappaport, Kissinger, Oppenheimer, Goldstein, Bernstein, Himmelfarb, Rosenthal and Loewenstein were North American names. After hearing about the Holocaust and learning what a Jew was from my best friend, a Jew, when I was sixteen and had moved to Vancouver, I began to understand why such names sounded German. I had thought that they were German names that somehow people had boldly insinuated into the powerful English and American language without succumbing to the ridicule or harsh, deliberate mispronunciations that I, audibly and perpetually a German, lived with. They were the names of successful immigrants. Now here they were on the stones of a Berlin graveyard.

Large parts of the cemetery have been rebuilt and refurbished—saniert, as the Germans call this activity—after falling into disuse and having no survivors to attend the graves, and Ilonka told me the local borough, in co-operation with the small Berlin Jewish community (now about 60,000 strong), were responsible for the reclamation. Much of the multi-acre site had not been saniert, and one could see tumbled stones, fallen pillars and marble slabs all jumbled together on the ground and being taken over by ivy. Once when Ilonka and her husband came here—something they did every year or two—they met a man who could hardly speak, was disabled and, it soon became apparent, was a camp survivor looking for evidence of his family. Thomas and Ilonka scrabbled with him through the dense ivy and the increasing concentration of willow, birch and poplar bush that had turned the outer, entirely unsaniert reaches of the graveyard into almost a jungle, and when eventually, after digging with their hands right down to the underlying earth, they found a fallen stone inscribed with the man’s family name, all of them wept.

Some of the Jews now living in Berlin returned in the 1950s and ’60s, many more immigrated from the Soviet Union after Glasnost, and quite a few live in the area around Hakescher Markt, which had been the Jewish quarter before the war. It was originally known as Scheunenviertel, “barn quarter”—a site, in the imperial era, of revolutionary upheaval, and in the 1920s of bohemian artistic fervour. Jews were Germany’s first multiculturalists: in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries they had come to Berlin from many European countries during the relatively tolerant Prussian and Wilhelmine eras, and fostered here the potent mix of cosmopolitan and communal identity, educated culture and economic muscle, liberal politics and intellectual sophistication that produced the great art and science Germany became known for, and which was such a threat to the Nazis. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Hakescher Markt became one of hippest neighbourhoods in Berlin, Eine coole, trendie, hippe Szene. Sehr in. Eine gechillte Atmosphäre. Ilonka had suggested that I go there to experience the now slightly subdued aftermath of this heady time in a formerly rundown East Berlin neighbourhood. Today it contains more small galleries—two, sometimes three on a block—than any other neighbourhood in Berlin, and cafés and bars where young people congregate and chat in many languages and in interesting groupings spill cosmopolitan enthusiasm out into the middle of the narrow, cobbled, almost traffic-bare streets. There are lots of bikes.

In a bar on Tucholsky Strasse a threesome speaking what I take, over the din, to be Polish liberally mixed with Englishisms, Germanisms and international cellphonese, sits at a table across from me. The two boys are beauties, right out of Visconti doing Thomas Mann (Death in Venice is playing in a local rep theatre), and they hold hands and play with each other’s fingers as the girl who sits between them, a beauty in her own right, takes first one and then the other fondly into her gaze, which is neither carnal nor matronly; I have no idea what—besides youth and beauty, and perhaps postmodernity—their gestures and sounds are intended to signify or communicate. At another table, a male voice rises steeply up into the din and gives full, mesmerizing meaning to the term basso profundo. The voice comes from a body expertly, casually, almost randomly—salopp is the German name for it—dressed in open-necked white shirt, black sports jacket, faded jeans, shiny dress shoes. The man’s jet-black hair—he’s, say, early forties—slopes down sideways across his forehead in a peek-a-boo style that requires him to stroke it back away from his eyes repeatedly with his hand—but just enough to be able to repeat the gesture moments later. His irresistible voice does not mask or overpower but holds within itself the ambience of the entire sonic environment. He is Russian, I decide: how could he not be? The woman across the table from him, who, judging from the movement of her lips, speaks during the pauses afforded by her tablemate, seems Russian also: she knows the vocal protocols. The two hold hands across the tabletop and frequently lean back in their chairs and laugh heartily, he from the chest, she, one imagines, from a place above her head.

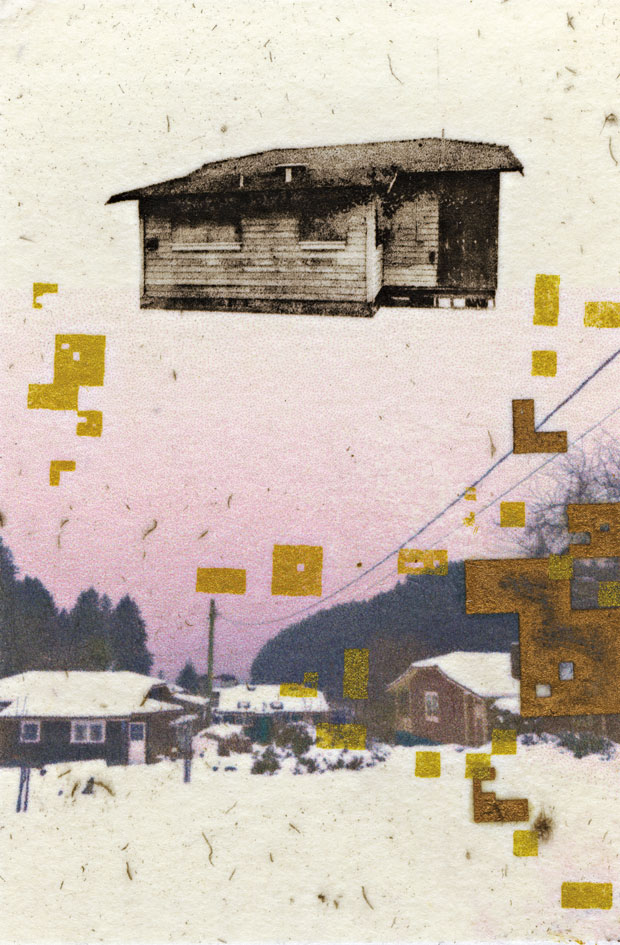

A few doors down along Tucholsky Strasse, young people sitting on the steps of the Pool Art Gallery drink champagne from plastic cups. They are attending the opening of an exhibition by a young woman named Michelle Jezierskyi, who, according to the program, was born and raised in Berlin by American parents and, as a result of her dual citizenship, produces art that “polarizes space and time” and invites the viewer into “impossible atmospheres and spatial landscapes” featuring houses that “float through space and hover inside caves; architecture is used as a metaphor for the outside within.” The talk in the gallery is mostly English in various accentings, modulating occasionally into German, and I feel for a time that the movement between these two languages, which has been such a determining and complex force in my life, is suddenly airy and easy, light.

It is a shock, then, to walk farther along Tucholsky Strasse and encounter a set of red and white metal barricades that spread from the sidewalk into the cobbled street in front of a building that reveals itself on second glance to contain a restaurant: Israelisches Restaurant, reads the sign above the door. An armed Berlin policeman patrols the area behind the barricades, and young people move in and out of the doorway, laughing and talking in Hebrew. I have to stop because the easy, touristy movements my body has adopted, full of joie de vivre and calm pleasuring, have stopped working. The kids seem unaffected by the barricades and the cop: they open their packs for inspection without interrupting their conversations and seem unaware of the situation’s—well, for me—profound incongruity. Once, in Israel, I had experienced a similar moment: a group of Israeli soldiers, boys and girls as I thought of them, in a shopping mall in Jerusalem, leaned over an arcade video game. Their Uzis hung across the backs of their beige uniforms as they played and laughed and smoked and chatted, there among the commodities. I learned later, from my host there—the friend who had told me about the Holocaust when we were sixteen—that this was daily life in Israel, a country protected by its youth, and I should not be afraid of weapons. When his eighteen-year-old daughter came home from duty that evening in her beige uniform, carrying her own Uzi as if it were a schoolbag, my education was enhanced yet again.

Later on Oranienburger Strasse I see the scene repeated in larger proportion in front of the Centrum Judaicum Neue Synagoge, a cultural centre, memory centre, art gallery and renovation of the bombed-out Neue Synagoge, Berlin’s main prewar synagogue that was inaugurated in 1866—in the presence of Otto von Bismarck, Germany’s “Iron Chancellor” and father of a nation that was one of the most tolerant in Europe toward Jews at the time. Red and white barricades thrust out incoherently amid the closely ranked restaurant tables that all along this tourist strip take up most of the sidewalk space and on this night are chock-full of exuberant foreigners; the empty space between the barricades and the building, for some reason partially covered with a strip of red carpet, is patrolled by three armed Berlin policemen. I wanted to ask them why they are there—perhaps a dignitary is visiting, or there has been “an incident”—but when I try to make eye contact, the cops or I—I don’t know which—look away just before contact.

All of the Jewish and Israeli establishments in Berlin, Ilonka later tells me, are guarded by Berlin police, mostly out of fear of anti-Israeli terrorist attacks and, to a lesser extent, of skinhead vandalism. The skinheads, she says, are of course much less organized than the jihadists, and don’t have the level of technology to do more than deface property and beat people up. The barricades are not given as much notice by Berliners as they are by visitors. The only other barricades I saw in Berlin—large ones, patrolled by soldiers with automatic weapons—circled the American and British embassies in the centre of the city, where all traffic is redirected.

In the centre of the Holocaust Memorial just south of the Brandenburg Gate, I descend a narrow set of stairs that I presume will lead me to the isolation chamber that I have mistakenly understood to have been created there. At the bottom of the stairs I can see a closed door with a sign that reads Notausgang, Emergency Exit, and I can’t tell whether the message is to be taken literally, metaphorically or ironically. The door seems to lead into the centre of the earth, and halfway down I grasp the handrail, hold tightly, begin to shake and turn back. I have read that the purpose of the chamber I imagine to be there was to convey the choking isolation experienced by concentration camp inmates, especially in those last moments before they entered the gas chambers.

I wander through the vast maze of rectangular grey stone slabs of varying heights—arranged in a grid and set upright, suggesting gravestones—that constitute the memorial, and although I “know” this is art, this is metaphor, this is aide de memoir, I feel a kind of continuing panic. Other people can be seen only in brief glimpses, almost photographic “takes,” as we move in and out of each other’s view in the narrow, undulating cobbled passageways between the slabs—which themselves grow taller as one approaches the centre of the exhibit—and I want to call or reach out to their distant and increasingly fleeting presences. Some of them, mostly young people, are indeed snapping photos of each other as they emerge suddenly from a passageway and then disappear just as suddenly into another, and I feel for moments like a participant in a game of virtual peek-a-boo, or photo tag.

It is impossible to know what people in their twenties with digital cameras, phone cameras, iPhones, etc., are thinking when they move, touristically, through such a memorial, which has something to do with their ancestors and no immediate connection to their present multimediated reality. On the southern edge of the monument, where I emerge, a group of what I think (did I hear Hebrew?) to be Israeli twenty-somethings are relaxing, talking, taking snaps of each other and chatting on their cellphones. Their bodies rest easily on the slabs, which here are flat and broad and at bench height, and as they lean against their packs and the stone slabs and each other, and talk and touch and smoke cigarettes, I have an uneasy and relieving sense of lightness. Some minutes later a tour bus stops nearby and groups of elderly passengers emerge; some of the men wear yarmulkas, They stand along the edge of the memorial and begin taking pictures: they aim their cameras high, over the whole monument for wide-angle panorama shots, and some of them pose in small groups in front of one or two of the slabs. Only a few of them sit down on the slabs, and even fewer of them move into the memorial, toward the centre.

I learn later that the isolation chamber I imagined to be in the centre of the Holocaust Memorial is in fact on the first floor of the Jewish Museum, a kilometre or so away on Linden Strasse. The place is called Memory Void and is filled with recorded sounds of clanking metal and a sea of a thousand grimacing masks, and you reach it after traversing a complicated sequence of architectural events by which the designer, Daniel Libeskind, has attempted to tell, in three dimensions, the difficult story of Germany’s Jews. The ground plan of the museum is in the shape of a lightning bolt that mimics and at the same time deconstructs a Star of David (so I am told) and it is (I am also told) a building in which it is easy to lose one’s way. The door I saw and was afraid to open in the heart of the memorial, it turns out, is, as my guidebook duly informs me, the planned entrance of “an underground centre where historical and personal accounts and life stories of some Holocaust victims will be presented.”

Ilonka tells me that many Berliners and other Germans criticized the Holocaust Memorial near Brandenburg Gate not only for its location but also because its memorial purview excludes non-Jews—the gypsies, homosexuals, communists, disabled people and prisoners of war—who were murdered in the camps. She says that its monumentality, reflected in its location and cost, seems to weaken its intention and transform it into a monument to guilt, in the name of a category of persons rather than the actual persons who were murdered; it seems to be addressed to an abstraction: the German people? the state? humanity?—who exactly does it hold responsible for the crimes? Ilonka asks. She says many young Germans (I imagine Ilonka to be in her thirties) consider it to be yet another attempt by German state and corporate authority to generalize and slide Holocaust responsibilities away from their institutions, and from individual persons, and foist them on subsequent generations like a kind of original sin.

On a rainy day I went looking for Bebel Platz in front of the German Opera House, where on May 10, 1933, Nazi Party functionaries under orders from Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels burned tens of thousands of books by Heinrich Heine, Erich Maria Remarque, Thomas and Heinrich Mann, Stefan Zweig, Erich Kästner, Bertolt Brecht, Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, H.G. Wells, Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein, Karl Marx and many others, German and foreign, on the grounds that their writings were “un-German.” When I got there, groups of cyclists were riding their bicycles back and forth over a glassed-in aperture, about a metre square, embedded in the cobbles, and which, when you looked down into it, revealed the ghostly catacombic apparition of a set of library shelves, bereft of books. The cyclists, some of whom rode rental bikes with fat balloon tires and wide Harley-style easy-chair handlebars, and others mountain bikes and even ten-speed bikes, would first imprint their tire marks in multiple patterns on the glass, and then park their bikes in a circular formation, still sitting astride them, and converse atop this historical, tender, modest and hallucinatory monument to literacy. When I arrived I didn’t know where the memorial (created by Misha Ullman) was, and it was only when I stepped right into the midst of the cyclists and saw a young man running his bicycle back and forth over the glass, leaving distinct water-and-mud markings, that I realized this was the place I had heard and read about.

How could one have guessed? In Egypt groups of youths often congregate around sites that contain “relics” and attempt to sell tourists examples of what they are talking about, but here there were no objects; there was simply a location in which events had occurred and in which, in view of or in memory of such events, one was encouraged to congregate—and in which kids talked. The youths on their bikes did not look to me like readers, but they did look like acute readers of “reality,” if such a text can be imagined by people of my generation, who have been taught to identify with and locate imagination in the pages of books—the very ones whose absence was here being celebrated and mourned. What texts were these young people tracing on the glass above the bookless library on Bebel Square, among cobbles and rain, among tourists, locals, riffraff and—dare I say it—complete strangers, where history has paused and trodden?

On the expansive, sloping, granite-paved courtyard in front of the Kulturzentrum, where I have just come out of the Gemä ldegalerie, Berlin’s premium collection of European paintings from the Middle Ages to 1800, a group of youths is assembling for what looks to be a skateboard competition. The courtyard slope reminds me of the racked stages of some Elizabethan-style theatres; it is interrupted by occasional small ledges, and in other places stone stairways, arranged in sets of two and bordered by magnificent knee-high stone banisters. All these lead downward into the courtyard’s expanse. It is perfect skateboarding territory.

A number of the youths carry expensive-looking camera and video equipment, which they remove from tattered packs as they set up around one of the double stairways. One group stands on a small roof beside it, arranges tripods and screws on camera lenses; another group fans out below, about twenty metres down from the stairway base. They park their boards by turning them at an angle against the grade of the courtyard slope, and set up their tripods and cameras there like professional media getting ready for a shoot. There is much banter and waiting, as on a movie set.

And then I hear a distant rumbling. It is a familiar sound: I know it from the skateboarders in my neighbourhood in Vancouver. The sound emanates from the tiny wheels; it resonates briefly in the cavity between board and stone, gains amplitude and then zooms, complete with Doppler effect, past your eardrums in a high-pitched roar as you involuntarily turn your head and see a youth flying. He has leaped, with his board, off the edge of the upper stairway, a good two or three metres above the sloped area at the foot of the second stairway; he lands there with a great clap that turns into a chatter as the board rushes out from under him. He lands on his feet, backwards on the granite, staggers back to catch his balance and then twirls on his heel, adjusts his cap and walks off toward some spectators who have joined the camera crew. A member of this crew catches the runaway board with his feet, and with a swift kick-like motion he propels it back up to the flying boarder, who overtakes it with his toe, tips it up and sideways with a smart crack, and catches it at his hip with his hand, never once breaking stride or looking down.

He goes back up to the starting point, the exit from the Gemälde Galerie where the courtyard’s slope begins. He works up his momentum, hops on just before he and the board reach the edge of the top stair, and flies off. But the board twists slightly and he lands without it, off balance, on the granite. He does a backroll, jumps to his feet and heads back toward the spectator row as the team down below shoot the board back up to him.

This scene is repeated twenty times or more. Each time, the boy—he looks about sixteen, he’s small and wiry, tattooed up both forearms, in a nondescript pair of grey sweats and a blue T-shirt with a big yellow banana on the front and a stylish visor cap that never falls off—leaps, the board flips and careens, jackknifes out from under him, he lands on the granite, he gets up again and walks away from the course.

Each time, the camera guys and the audience cheer and then groan. After ten failures the boy starts cursing, loud enough to produce an echo from the Gemä lde Galerie Walls. Fuck you. He’s not English-speaking, though. He and the others speak a kind of German that I can catch only snippets of: part dialect, part skater talk, part English cursing (which may be part of skater talk). Youthese.

Then finally, at a moment like any other, the boy jumps on his board and rises like a skylark, curving in the air. The board lands beneath him with a kerclank, and he lands on it, sways backward for a moment, lurches, catches his balance, and then, fully in control, cruises like a motorboat into the applauding ranks of the film crew. The guys on the roof beside the stairs and the audience on the sidelines pick up the cheering and clapping, which echoes from the walls of the Gemä lde Galerie.

Then the whole thing is over. The shoot is in the can. Everyone packs their cameras back into their low-tech packs, folds their expensive-looking tripods as if they were camping stools, chats a bit and then leaves in small clusters. They tuck their boards, which are fiercely decorated with graffiti-style designs, under their arms and walk off toward the Matthäus Church nearby, where the life of a Lutheran minister who resisted the Nazis and died in the camps is being memorialized in a historical display. The bell of the reconstituted church tolls on the quarter hour. Potsdamer Platz, the fiercely branded, up-market space station built after the Wende (fall of the Wall), rises up in the background, and the Sony and Mercedes Benz Centre monoliths can be seen bordering off and securing one’s view of the horizon.