.svg)

Mary Meigs is one of eight women who portrayed themselves in The Company of Strangers, a film directed by Cynthia Scott and written by Gloria Demers, with Cynthia Scott, David Wilson and Sally Bochner. The movie was released in 199. Filmgoers named it the favourite at the Vancouver Film Festival, it was second most popular film at the Toronto Festival of Festivals, the Halifax Film Festival awarded its eight stars the Best Actress prize, and it was named Best Film at the Mannheim (Germany) film festival. Cast members, who did not know each other before filming began, were Alice Diabo, 74, a Mohawk Indian born on the Khanawake Reserve; Constance Garneau, 88, born in the U.S. and brought to Quebec by her family; Winifred Holden, 76, an Englishwoman who moved to Montreal after World War II; Cissy Meddings, 76, who was bom in England and moved to Canada in 1981; Catherine Roche, 68, a Roman Catholic nun born in the U.S. who joined the Order of the Sacred Heart in Montreal; Michelle Sweeney, 27, a jazz singer from Montreal; and Beth Webber, 8, who was born in England and moved to Montreal in 193.

Our film is a semi-documentary. We are ourselves, up to a point; beyond this point is the "semi," a region with boundaries that become more or less imprecise, according to our view of them. In one sense, it is semi from beginning to end, for we wouldn’t be out there in the wilds, wouldn’t have boarded the bus together. Semi has worked to put together seven old women and a young woman who would never have known of each other’s existence, with the ironic outcome that both in real life and on film, we become friends who now need to keep in touch with one another. A real documentary might not have had this effect: it might have isolated each of us in her own life and surroundings. Out there on the three locations, links between us are forged in every scene. Consider two scenes from the shooting schedule, July 4th through 8th:

#64: Tosses pills (Constance)

#69: Fishing with rocks (Cissy, Mary, Beth)

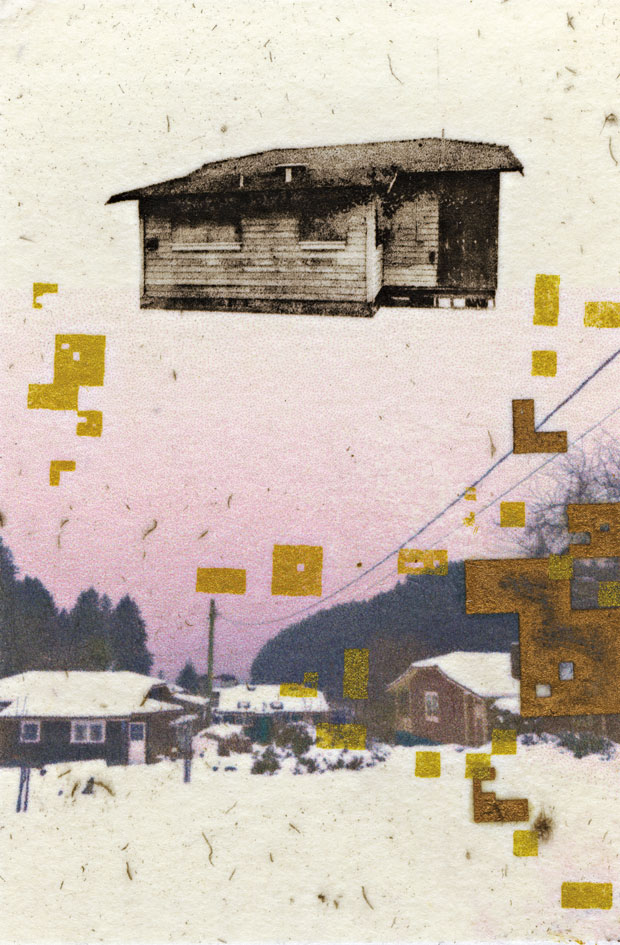

Both nutshell scenes contain a kernel of intractability by one of us: we balk at crossing the border into the semi. In #64, Constance is supposed to feel so rejuvenated by the sight of her childhood "water-house," as she calls it, and by memories of happiness there that she impetuously tosses her pills into the lake. "But I wouldn’t do that," she says. "I’d be afraid I might need them." I, too, knew that even if I felt rejuvenated, I wouldn’t throw away my pills. Old people cling to their pills. "Constance, just go ahead and do it, please," says Cynthia. "We can decide later." Later, in the cutting room where our fate is determined.

"I hope you’ll finish your snake," says Cynthia to Winnie at breakfast, "and then we can have the scene where you stuff it with grass." Winnie is knitting away on one of her brightly striped woollen snakes, which she stuffs with cotton batting. "Oh, I can’t do that," she says, for even in fantasyland she won’t stuff one of her snakes with grass. The art of snake-making has its rules. We all have rules, though we don’t know what they are until we are asked to transgress them. Take Fishing with rocks (Cissy, Mary, Beth), a good example of mildly indigestible semi. The three of us are standing at the edge of the calm lake, our feet planted well apart so that we won’t topple into the water when we heave our rocks, which we hold in readiness. Looking down we see very small fish swimming in our shadows. "And—camera!" cries Cynthia, the signal for us to shout in unison, "One, two, three!" The waves made by our rocks ripple right up to our toes. With absurd solemnity we peer into the ruffled water. "It didn’t work," I say gloomily. We do this scene over three or four times in a conspiracy of pretence. Personally, I’m ashamed of being caught doing something so dumb. "We’ll have pate of trout," I say, and we laugh.

"But I’d never wear anything like that." This is Catherine pronouncing judgement on the baggy grey cardigan that has been judged suitable for a nun, though her personal choice would have been closer to the plumage of a South American macaw. The distinctions we make between real and semi, between what we will and won’t do, like or don’t like, are perfectly clear to us. We are asked one by one, how do you feel about walking nude into the lake? That’s how I understood the question, though Cynthia tells me that it was hedged with delicate precautions, which, in my panic, I didn’t even wait to hear. My horror of the idea must go back to the irreversible prudery that was instilled in me seventy years ago. I reason with myself; I think of a painter friend, older than I am. In a documentary about her life, she walks naked down a beach and plunges into the sea. How I envy her freedom!

There are other no’s in the domain of our dignity as old bodies, unworthy (some of us think) of display. Our vanity, too, is a factor, and the interiorization of supposed reactions an audience might have. "Grotesque, ridiculous, they’re trying to make a laughingstock of us," says Constance about our splashing scene: she is looking through the eyes of a hostile audience. But the camera keeps rolling while we (Cissy, Alice and I) become ourselves as little children and, fully clothed, chase each other into the dazzling lake, scooping up warm water as we go. Alice goes in up to her waist, heaves gallons of water at Cissy and me; Cissy and I shriek in mock terror.

This scene, which gave us such joy and embarrassed Constance, vanished, and then reappeared in the final version. There were delicate feelings of rightness and wrongness to be considered in the cutting process, a sure instinct that spotted whatever was sentimental, over the top, inappropriate, boring. Not always agreement, of course: viewing the rushes over a thousand times, they would take something out or stick it back in again. Meanwhile, Constance’s dismay, which weighed so heavily with her, made her repeat the words grotesque, ridiculous, we have nothing left but our dignity—to anyone who would listen. "Don’t you agree? No, I see you don’t," for I was answering her "everybody will laugh at us" with "they’ll laugh with us." How could they laugh, except with us, at our joie de vivre? I doubt if Constance’s dismay weighed heavily in the decision to cut. Since we didn’t know the criteria, we were the worst judges of what worked and what didn’t work. We were being trimmed and shaped out of thirty hours of filming, reduced from miles of film to inches. Now and then the editors must have been startled by an audible squeak when their scissors cut through one of our cherished scenes, those scenes that still have a ghostly presence in our minds.

During the filming, however, there are times when one of us wants a scene cut—this, too, from a sense of what is appropriate, of which each of us is a judge. Thus Catherine, who somehow gets wind of the bootjack scene and learns enough about it to feel outraged. The scene consists of the demonstration of a cast-iron bootjack in the shape of a buxom woman with legs spread, an item supposedly found in the barn. In reality, Gloria had found it in an airport boutique, and had been intrigued by its inherent violence as a sexist artifact. Something for the film, she must have thought. To pull off a boot you have to put one foot on the woman’s face and the booted heel of the other between her legs and give a quick jerk upwards and backwards.

Winnie, Cissy, Alice and I are examining the thing. What can it be? they ask. I say it’s a piece of nineteenth-century pornography and explain indignantly how it’s used (Gloria has told me), and we try it with Winnie’s foot shod in its little yellow shoe. All of us are surprised when it works to perfection. "Ow!" cries Cissy, "what a thrill!" "Oh, Cissy, you’re impossible," I say. Afterwards, Catherine draws each of us aside and gives each the same piece of her mind. What is the scene doing there? It’s demeaning, it’s gratuitous feminist propaganda (this is like a dagger in my heart), it does violence to the spirit of the film. And, even in the heat of battle, I begin to think perhaps she’s right. What is it doing? Isn’t it the only strong dose of feminism in the film? Moreover, in the scene, I’ve worked myself up to a pitch of indignation (am I grotesque? Ridiculous?). I begin to be glad that Cissy laughed, with her laughter like a delighted child’s. She hasn’t seen the point; out there in that place that seems remote from boots on faces, boots jammed between women’s legs. Can I legitimately use a piece of cast-iron in the shape of a woman as a pretext for a little lecture? Though they all look shocked by the way this old piece of cast-iron is put to use, and Alice says, "That’s not right," none of them wants to share my anger; it embarrasses them (I say to myself).

A few days later Gloria, having seen the rushes, says, "You’ll be glad to hear that the bootjack scene has been taken out." A week later it is in again. And it is still in when we are shown the finished film, though the feminist message has appeared and disappeared. The same happens with many of the scenes that have had special import for us. In the cutting process they have become glancing and light-filled like fragments of a mirror flashing in the sun. They become very small facets of the whole, each with an identical importance, or elements of the composition that are held on the picture-plane by their place in the whole. So it’s painting they’ve been doing, I think, or it’s music. I begin to understand the editors’ responsibility to eliminate negative or dead space. A scene that is even a minute too long becomes dead space; in this space a spectator has room to writhe with boredom or impatience. If the space is thought of as music, it may contain the right to linger in an adagio passage—say, the flight of a night heron across the evening sky. The heron is allowed to fly from east to west, and her leisurely beating wings carry messages about life and death and the meaning of the film. Her flight corresponds to the adagio scenes in which we talk about our fears. Birds and landscape in the film bear a burden of explanation that is as light as air: the heron’s flight, the song of the white-throated sparrow, the early morning mist illuminated by pink sunlight. Now and then they serve as the expression of our hopes and fears; the cry of a bird is a synonym for Beth’s terror of night in the country, and the song of the white-throated sparrow, which Constance can no longer hear, a synonym for the losses of old age. It is singing close by; she listens and does not hear it. "They used to be everywhere," she says.